Most of the time when ruminant animals can’t deliver by themselves, it is either that the foetus is too being to pass through the vagina of the female or that the female has a small genital opening that the foetus cannot pass through.

It is also possible that the foetus presented a wrong position and posture e.g. if the foetus tries to come out through the leg and one is still inside while the other is outside. All of these will make it either difficult or impossible for the female to deliver on its own.

Therefore the kind of help to render depends on the extent of the difficulty the female is having in delivery. If it is minor, manual manipulation may be done to pull out the foetus.

However, if it is complicated, there may be need for surgical operation which will require the service of a Vet. Doctor. One should be consulted immediately for necessary assistance if the need arises.

Read Also: Ruminant Animal Wounds: Causes and Methods of Treatment

Birth and Reproduction complications in Ruminant Animals

There are various diseases and abnormalities that affect the reproductive system of domestic animals. These diseases commonly result in early embryonic deaths, abortions, mummification and infertility.

Following the infectious disease, animals may end up with other related conditions such as Endrometitis and Pyometra. All these result in lost income to the farmer as the animals may be unable to give birth again.

Brucellosis and Q-fever are described under the Chapter Abortion and Stillbirth, are also highly contagious, and may transfer to people causing agonizing pain and sickness and very expensive medication, so paying close attention to the reproductive health of your animals is highly recommended.

Non-infectious conditions and other abnormalities include:

a. Anoestrus

b. Silent heat

c. Freemartinism

d. White heifer disease

When a herd of cows or sheep tend to have reduced number of calves, longer time before the female becomes pregnant, as well as when frequent abortions are observered or suspected, it is likely that a genital disease could be the problem.

Farmers would in such cases be advised to invite a veterinarian to investigate the herd and take samples for analysis that can determine the cause of the problem. Reduced fertility in a herd means less profit and slower build up of herds.

Genital infections are spread through sexual contact between male and female animals. Unsually infected males do not show signs, but they can spread the disease to the female.

(1) Retained Placenta in Ruminant Animals

Description

After giving birth cows sometimes do not drop the afterbirth (placenta) immediately. This can cause problems as decaying placenta tissue can cause a serious bacterial infection of the cow and if untreated the cow can even die.

Normally expulsion takes place within 3-8 hours after delivery of the calf.

Retained placenta is a common complication after calving; if the cow doesn’t shed those membranes within about 12 -24 hours, it’s considered to be “retained.”

Call a veterinarian after 12 hours to judge the situation and watch your cow closely. dont remove the afterbirth manually (see further below under treatment).

The incidence of retained placenta in healthy dairy cows is 5 – 15%, while the incidence in beef cows is lower.

Cows which fail to drop the afterbirth within 36 hours are likely to retain it for 7 -10 days. This is because substantial uterine contractions do not proceed beyond 36 hours of the birth of the calf and if the membranes have not been expelled by this time their subsequent separation from the uterine wall can only occur as a result of the rotting of the afterbirth connections to the uterus and their expulsion then depends on the speed of the normal shrinking of the uterus.

Diagnosis and Symptoms

1. This is normally straightforward. Degenerating, discoloured and increasingly unpleasant-smelling membranes are seen hanging from the vulva more than 24 hours after calving. Occasionally the retained membranes may remain within the uterus and may not be readily apparent, but their presence is usually signaled by a foul-smelling discharge.

2. Milk from cows with retained placenta must not be used for human consumption.

3. Usually there is no systemic illness. When there is, it is it is related to toxaemia (blood poisoning). Symptoms may include fever, lack of appetite, depression, a reduction in milk yield, straining, a foul smelling vaginal discharge and diarrhoea. These symptoms are more likely to occur in cases where retention follows extensive interference as in a difficult calving.

Causes

1. The risk is increased by abortion, difficult calvings, milk fever, twin births, advancing age of the cow, premature birth, inflammation of the placenta and various nutritional disturbances. With regard to the latter it should be noted that deficiencies of selenium, Vitamin A, copper and iodine increase the incidence of retained placenta. Providing selenium prior to calving reduces the incidence of retained placenta.

2. There is a genetic implication and cows which retain their placenta in the presence of a nutritionally balanced diet and giving birth to a calf of normal size and with no complications should not be considered for further breeding.

3. The incidence is higher in overweight cows or in cows that are too thin, check for the weight because it may be responsible for the placenta retention.

Treatment

1. Generally speaking uncomplicated cases of retained placenta require no treatment.

2. Some veterinarians are of the opinion that treatment should only be considered if the animal appears to become sick (beginning blood poisoning).

3. Manual removal of retained foetal membranes in the cow is NOT recommended, is potentially harmful, and can be a source of infection in the uterus.

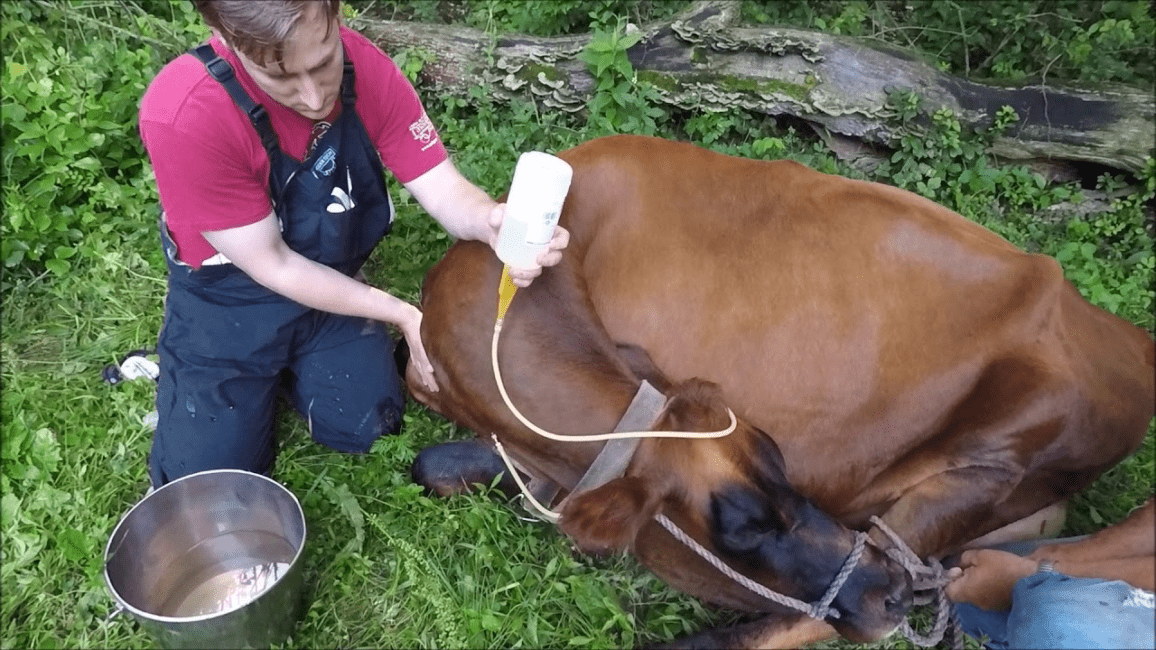

4. If the afterbirth is retained (does not drop as normal within the first hours after calving), let the calf suckle many times or stimulate the udder manually, because this releases the hormone oxytocin which also help in releasing the afterbirth.

5. If this does not help, keep an eye on the cow that she does not get ill, and wait for 12 hours then call a veterinarian to judge the situation and treat the animal if relevant. Sometimes the uterus can be stimulated by massage by rectum, and the veterinarian can do this. In many cases, the veterinarian can stimulate give a hormone which contracts the uterus, and this is enough for the cow to release the afterbirth.

6. If a retained afterbirth is not treated it can potentially cause severe infection of the mother and lead to death or infertility. The veterinarian will judge the risk and may treat with antibiotics to avoid that situation. In some cases, the remainings of the afterbirth comes when the cow is in heat first time after the birth, and it may cause a delay in getting pregnant again, but without other complications.

Read Also: Worm Infestation on Ruminant Animals: Symptoms and Treatment

(2) Milk fever in Ruminant Animals

Description

Milk fever is a condition of mature dairy cows that occurs a few days before, but mostly immediately after calving. It is common in imported high yielding dairy cows, especially Friesian or Channel Island breeds such as Jersey or Guernsey. Milk fever does not occur in indigenous cows.

Milk fever is caused by low calcium levels in the body due to the sudden onset of lactation at calving. The nutritional status of the cow in the dry period is known to influence the risk of the disease. Diets low in dry matter such as lush pastures and diets with high calcium during dry period can predispose the cow to milk fever. Low magnesium in the diet hinders absorption of calcium and hence predisposes the cow to milk fever.

The disease almost only occurs in cows which are in their third lactation or older. It is very rare in calving heifers.

Signs of Milk fever in Ruminant Animals

1. The first sign of the disease is loss of appetite, followed by a slight drop in temperature.

2. The affected animal become uncoordinated, falls over and remains seated with its head resting on its shoulder.

3. Dull eyes and shivering, constipation is a common feature and sometimes a wobbly gait is seen.

4. If not treated immediately, the animal may go into coma and die within a day after the first signs. Since the rumen stops functioning, bloat becomes a complication and may cause death

Diagnosis

1. Based on history, recent calving or near calving

2. Clinical signs and response to calcium treatment

3. Blood samples can be taken to the laboratory for calcium and phosphate levels

Diseases with similar symptoms

1. Differentiate diagnosis with Ephemeral Fever (please insert link) where the cow goes recumbent (insert dictionary)

Prevention and Control

1. Feed the cow with the correct levels of nutrients from late pregnancy to peak lactation

2. Feed diets with the right dry matter content such as offering additional hay in combination with lush pasture.

3. Feed balanced mineral supplement which appreciates the inter-relationship between calcium, phosphorus and magnesium The minerals for a dry cow should be different from the minerals for a lactating cow.

4. Right after successful calving give high yielding cows a handful of agricultural lime mixed with first feed. This will assist the cow in summoning enough calcium to produce milk.

5. Let the calf suckle for the first 3-4 days with no extra milking. This will allow the cow to adjust gradually to produce milk. The first colostrum is not marketable anyway.

Recommended treatment

1. Be aware of the first signs: The cow has no appetite and becomes cold. Feel the ears, the basis of the horns and the head: if it is cold, the cow is developing milk fever. At this stage, the stomachs of the cow still can work in many cases – not all. If the stomachs work, it can sometimes be successfully treated with fluent calcium in water given in a bottle. If the stomachs do not work, then this is useless, and calcium has to be given as described below.

2. If the cow is found to be lying on her side she should be immediately propped on to her chest, otherwise she is liable to get bloat or inhale stomach content with the attendant risk of developing aspiration pneumonia. DO NOT use rocks or boulders to prop!

3. Call veterinary immediately

4. Slow intravenous infusion 400ml of 20% calcium borogluconate should be administered as early as is possible. If this is difficult then give the same volume by subcutaneous (insert dictionary) injection. Give in several sites and massage the sites of injection to disperse the solution.

5. Response to treatment is seen by the cow belching, snapping and opening her eyelids, breathing deeply, passing dung and sitting up.

6. Even if the cow appears to be unconscious give intravenous calcium. Even cases which look hopeless can recover.

7. The calf should be removed and the cow not milked for 24 hours. On day two milk half the estimated volume from each quarter and feed this to the calf. On day three milk normally. If the calf is allowed unrestrained access to the cow or if unrestrained milking is carried out the cow may well go down again.

8. Get a flutter valve and have it clean and ready for use. There is nothing more frustrating than trying to give 400 ml calcium by intravenous injection with a 20 ml syringe and it is guaranteed to damage the jugular vein.

(3) Causes of infertility in Ruminant Animals

Causes of infertility can be very many. Below some of the more common ones:

Read Also: How to Identify the Particular Disease Affecting your Ruminant Animals

(4) Anoestrus in Ruminant Animal

Anoestrus is a condition where some cows do not show heat signs for a long time after calving. In this case, no ovulation takes place. The condition can be caused by an infection or inflammation of the uterus and underfeeding of the cow, especially with minerals.

Diagnosis

1. Rectal examination by qualified veterinary to determine the cause.

Prevention

1. Proper feeding and mineral supplementation of dairy cows including:

2. Adequate quantity and good quality roughage.

3. Adlibitum mineral supplementation.

Treatment

1. Treat the underlying cause. See Endometritis below.

(5) Endometritis in Ruminant Animal

This is the inflammation of the endometrium (internal lining and mucus membrane of the uterus). It occurs as a result of an infection by microorganisms.

Infection normally occurs during mating or around labour and delivery by such organisms as Campylobacter fetus (See Brucellosis) or Trichomonas fetus (See Leptospirosis) and other opportunistic bacteria like the Corynobacterium pyogenes, E. coli and Fusobacterium necrophorum.

Endometritis often occurs following difficult or abnormal labour or delivery and/or retained placenta.

Clinical Signs

1. Discharges.

2. Repeated heat after mating.

Diagnosis

1. History of repeated heat.

2. Difficult calving.

3. Retained placenta.

Prevention and Control

1. Routine and strict hygiene at calving:

2. Cows should be kept clean at calving

3. Ensure that calving boxes are cleaned and disinfected

Treatment

1. Treat the underlying cause according veterinary advice

(6) Pyometra in Ruminant Animals

This condition is due to an accumulation of pus in the uterus and can occur after chronic endometritis or may result from the death of an embryo or fetus with subsequent infection by Corynobacterium pyogenes bacteria. The situation may persist undetected for some time and may be confused for pregnancy.

Clinical Signs

1. Enlarged uterus.

2. Discharge of pus when the cow lies down.

Diagnosis

1. Uterus palpataion by a veterinarian.

2. Uterus scan

Recommended Treatment

1. Treatment used by estrogens and oxytocin according to veterinary advice.

(7) Epivag in Ruminant Animals

Common Names: Infectious epididymitis, Cervici-vaginitis

Epivag is a rare chronic venereal infection of cattle probably caused by a virus. It occurs in East and Southern Africa. In the 1930s the disease was rampant in Eastern and Southern Africa, prompting the creation of the world’s first national AI service to control it in Kenya. It has now become sporadic and reports are unusual.

The infection is spread by coitus or contaminated obstetrical (veterinary) equipment.

Signs of Epivag

1. Epivag is characterized by enlargement and induration of the epididymis in the bull and vaginitis, cervicitis and endometritis in the cow.

2. Only exotic cattle are affected. Indigenous African cattle possess a high natural resistance and signs of Epivag in them are rare. Imported exotic cattle and their crosses have little resistance.

3. Affected bulls have enlarged and distorted testes. The lesions take 3-6 months to develop and sometimes longer. Enlargement of the head and tail of the epididymis occurs. Often both epididymses are affected. Bulls are at first infertile and then sterile. The semen is affected before clinical signs are apparent. The volume is reduced, the appearance is watery and floccules of mucus appear.

4. The incubation period in cows lasts only a few days but the infection persists for months. In cows, the clinical signs vary from slight reddening of the vagina with little or no discharge to severe inflammation of the inner lining of the vagina, cervix and uterus with profuse thick yellowish discharges. Infection usually persists for several months in cows with most of them recovering while a few may become permanently sterile.

Diagnosis

1. Diagnosis is based on the herd history, the clinical signs, and the semen examiniation. Lesions in the female are difficult to assess in the absence of the disease in the male.

Diseases with Similar Symptoms

1. The clinical signs in the female are easily confused with those of Infectious Pustular Vulvovaginitis. Lesions in Epivag, however, persist for many weeks.

Prevention and Control

1. Use of artificial insemination with semen from clean bulls is an effective control measure. All affected bulls should be slaughtered (or not used for reproduction).

Recommended treatment

1. Because the specific cause is uncertain, no attempt should be made to treat the bulls, but cows can be treated symptomatically by a veterinarian and then later inseminated.

2. The widespread use of artificial insemination using semen from clean bulls has brought the disease under control dramatically in Eastern and Southern Africa.

3. Otherwise it is recommended to use indigenous breeds that possess a high natural resistance and rarely get infected.

Read Also: Signs and Diseases Ruminant Animals (Livestocks) get from Feeds and Water

(8) Freemartinism in Ruminant Animals

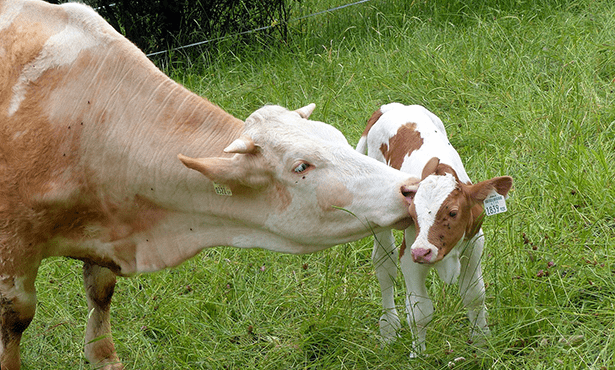

This is one of the most common reproductive abnormalities, mainly congenital, affecting female cattle. It occurs when both male and female conceptus are present in the same uterus.

In cattle there is a tendency for the placenta of twin fetuses to merge, thereby causing the circulatory system of the twins to become interconnected. This often affects the development of the female sex organs of the female twin probably due to the androgens of the male blood circulation.

Diagnosis

1. History of twin male and female calves.

2. Failure of estrus to occur.

Prevention and Control

1. Culling of freemartin heifers.

Treatment

1. None.

(9) Silent Heat in Ruminant Animals

Silent heat is the term used when a cow which has already shown heat signs shows them again after 6 weeks or later. The regular heat period at 3 weeks is often referred to as the silent heat. The heat signs might have been weak and therefore not observed.

If the cow has been inseminated before, she might have had an early abortion so that she shows heat signs again 6-9 weeks after the last insemination.

Clinical Signs

1. Small vulva.

2. Long tuft of hair at the ventral end of the vulva.

3. Clitoris is prominent when you open the vulva.

4. Complete anoestrus.

Diagnosis

1. Rectal palpation and use of breeding records.

Prevention

1. Proper feeding and mineral supplementation of dairy cows including:

2. Adequate quantity and good quality roughage.

3. Adlibitum mineral supplementation.

4. Timely and regular heat detection.

Treatment

1. Use of hormones according to veterinary advice.

(10) Trichomoniasis in Ruminant Animals

Trichomoniasis is a venereal protozoal infection of cattle caused by Titrichomonas foetus. It occurs without fever and is contagious. Trichomoniasis is confined to the reproductive tract of the cow and the preputial sac of the bull. The disease occurs worldwide.

The infection is spread by coitus or through the use of contaminated insemination instruments or stockmen’s hands.

(11) Vibriosis in Ruminant Animals

Scientific Name:Campylobacter fetus venerealis and Campylobacter fetus fetusCommon Names:Bovine campylobacteriosis, Genital vibriosis

Vibriosis is a bacterial venereal disease of cattle and sheep characterized primarily by early embryonic death, infertility, a protracted calving season and occasionally by abortion. It occurs worldwide.

It is caused by bacteria called Campylobacter fetus, Venerealis and Campylobacter fetus fetus. C. fetus fetus was thought for many years to be primarily an intestinal organism but it has been found to be a significant cause of the classic infertility syndrome usually attributed to C. fetus venerealis.

Vibriosis in sheep is evidenced by abortions in late pregnancy and still births.

(12) White Heifer Disease

This condition has been estimated to account for about 5% of infertility in heifers. The condition is an abnormality when the reproductive tract of white heifers gets blocked during development.

Unlike freemartins, the cow’s ovaries are well developed and functional and therefore heat and ovulation takes place normally. However, fertilization may not take place depending on the site of the reproductive tract that is obstructed.

Frequently Asked Questions

We will update this section soon.