This article provides an overview of an essential hereditary component of the cell: the chromosome. A chromosome is a thread-like structure composed of DNA and proteins. The diagrammatic structure and essential parts of chromosomes are explained in detail.

Read Also: How to Grow, Use and Care for Woolly Cupgrass (Eriochloa villosa)

Understanding Chromosomes and Their Function in Cell Division

Chromosomes are thread-like materials visible within the nucleus of a cell when stained at the appropriate stages of cell division. Each chromosome consists of protein and a single molecule of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). Passed from parents to offspring, DNA contains the specific instructions that make each type of living organism unique.

In other words, chromosomes are structures made of DNA and proteins, duplicated, and transmitted to the next generation through mitosis and meiosis. The term “chromosome” originates from the Greek words for color (chroma) and body (soma) due to the strong staining effect of certain dyes used in research.

The unique structure of chromosomes allows DNA to be tightly wrapped around spool-like proteins called histones. Without such packaging, DNA molecules would be too long to fit inside cells.

For example, if all of the DNA molecules in a single human cell were unwound from their histones and placed end-to-end, they would stretch 6 feet. For an organism to grow and function properly, cells must divide to produce new cells that replace old, worn-out ones.

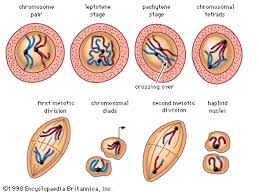

During cell division, it is essential for DNA to remain intact and be evenly distributed among cells. Chromosomes play a crucial role in ensuring DNA is accurately copied and distributed during most cell divisions.

Essential Parts of a Chromosome in Cell Division

The key parts of a chromosome, essential for cell division, include:

(1) Centromere, (2) Telomere, and (3) Origin of replication sites where replication forks begin to form.

1. Centromere: The Constricted Region of Chromosomes

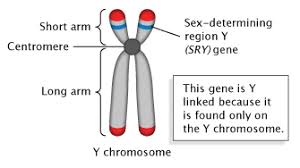

The centromere is the constricted region of linear chromosomes (Fig. 6). While it is called the centromere, it is not always located exactly in the center of the chromosome and, in some cases, is found near the chromosome’s end. The areas on either side of the centromere are referred to as the chromosome’s arms.

The centromere is the largest constriction on a chromosome and serves as the attachment point for spindle fibers during cell division. A chromosome without a centromere ceases to function as a chromosome because it cannot attach to the spindle, leading to its disappearance from the cell.

Centromeres ensure that chromosomes remain properly aligned during cell division. As chromosomes replicate in preparation for a new cell, the centromere serves as an attachment site for the two halves of each replicated chromosome, known as sister chromatids.

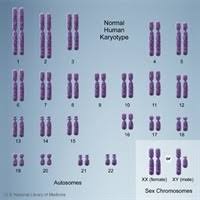

If the chromosome set is from a male, it contains an X and a Y chromosome; from a female, it contains two X chromosomes. All chromosomes other than the sex chromosomes are known as autosomes.

Human cells contain two sets of chromosomes: one inherited from the mother and one from the father. Each set consists of 23 chromosomes (22 autosomes and a sex chromosome, either X or Y).

2. Telomere: The Protective End of Chromosomes

Telomeres are repetitive stretches of DNA located at the ends of linear chromosomes. They serve to protect the ends of chromosomes, much like the tips of shoelaces prevent unraveling. In many types of cells, telomeres lose a bit of their DNA with each cell division.

When all of the telomere DNA is depleted, the cell can no longer replicate and dies. Telomeres, composed of many repeats of the TTAGGG sequence, shorten with each mitotic division.

White blood cells and other frequently dividing cells possess an enzyme that prevents telomere loss, enabling them to live longer than other cells. Telomeres are also associated with cancer, as malignant cells typically retain their telomeres, promoting uncontrolled growth.

Read Also: How to Grow, Use and Care for Woolly Sedge Grass (Carex pellita)

Chromosome Number in Mammals

The number of chromosomes varies among species, and the diploid chromosome count for some mammals is shown below

Diploid Chromosome Number of Some Mammals

| Common/Scientific Name | Number of Chromosomes |

|---|---|

| Human (Homo sapiens) | 64 |

| Horse (Equus caballus) | 64 |

| Ass (Equus asinus) | 62 |

| Cattle (Bos Taurus, Bos indicus, Bison bison) | 60 |

| Buffalo (Bubalus bubalus) | 48 |

| Ox (Ovbus moschatus) | 48 |

| Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) | 70 |

| Sheep (Ovis aries) | 54 |

| Goats (Capra hircus) | 60 |

| Swine (Sus scrofa) | 38 |

| Dog (Canis familiaris) | 78 |

| Cat (Felis catus) | 38 |

| Rabbit (Oryctalagus cunniculus) | 44 |

| Mouse (Mus musculus) | 40 |

| Rat (Rattus norvegicus) | 42 |

| Chicken (Gallus gallus) | 36 |

In conclusion, chromosomes are found in the nucleus of all body cells, except for red blood cells, which lack a nucleus and thus do not contain chromosomes. The two sex chromosomes, X and Y, determine the biological sex of an individual.

These chromosomes, along with the genes they carry, are composed of DNA (Deoxyribonucleic Acid). The essential parts of a chromosome, including the centromere, telomere, and replication origin, play critical roles in the process of cell division, ensuring the proper transmission of genetic material.

Do you have any questions, suggestions, or contributions? If so, please feel free to use the comment box below to share your thoughts. We also encourage you to kindly share this information with others who might benefit from it. Since we can’t reach everyone at once, we truly appreciate your help in spreading the word. Thank you so much for your support and for sharing!