Fish rarely suffer from bacterial diseases unless they are farmed or confined to a tank or bowl. In such cases, where stagnation, overcrowding, limited space, increased excreta concentration, and higher nutrient levels in the water are common, bacteria can thrive and cause infections.

Bacterial diseases in fish are difficult to handle, making early detection essential to prevent them from becoming fatal. These diseases are generally categorized into two types: primary pathogens, which are not usually found in the fish’s environment, and opportunistic pathogens, which are generally present.

Opportunistic bacteria are the most common and usually do not pose a threat unless the fish’s environment changes, such as the presence of decaying material or stress and injury to the fish. These factors allow bacteria to invade. In their early stages, bacterial diseases are often localized, with signs such as fin rot, body ulcers, and red or inflamed areas on the fins and body.

If untreated, these infections may become systemic, spreading through the fish’s body. This occurs by absorption through the gills, gut, or skin. Additional signs of bacterial infection include swollen eyes, a swollen gut, or lethargy. Gill disease can also indicate bacterial infection.

As bacterial infections cannot be accurately diagnosed by sight alone, tests such as mucus sample testing are important. However, visible signs can help narrow down possible problems. Fish store employees, other fish keepers, and veterinarians can offer helpful advice.

Read Also: 22 Medicinal Health Benefits of Nutmeg (Myristica Fragrans)

Common Bacterial Diseases in Fish

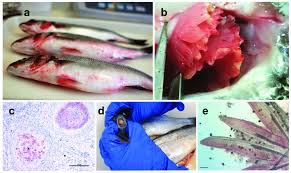

Bacterial diseases are often internal and require treatment with medicated feeds containing antibiotics. Infected fish may display hemorrhagic spots or ulcers on the body, eyes, and mouth. Other signs include an enlarged, fluid-filled abdomen and protruding eyes. External bacterial infections may result in skin erosion and ulceration. Columnaris is an example of an external bacterial infection that can occur due to rough handling.

One main goal in fish farming practices is to avoid and minimize stress on the fish. The aquatic environment is constantly changing physically, chemically, and biologically, and these changes, along with farming practices, can severely stress the fish. Stress in fish can lead to many bacterial diseases, especially in nursery, rearing, and grow-out ponds.

Several bacterial pathogens like Aeromonas hydrophila, A. salmonicida, Pseudomonas fluorescens, P. putrefaciens, Flexibacter columnaris, Edwardsiella tarda, Vibrio alginolyticus, and V. parahaemolyticus have been identified as common agents in fish diseases.

Bacterial Infections and Symptoms

Bacterial infections in fish are usually caused by pathogens like Vibrio, Pseudomonas, and Aeromonas. Symptoms of these infections include cloudy eyes, bloody patches, decaying or frayed fins, and scratching. Fish with internal infections may only show symptoms like loss of appetite and swollen abdomen.

Bacterial infections often affect all fish in a pond or tank, meaning the entire system may need treatment. Treating a large pond can be expensive. However, if one fish appears infected, moving it to a quarantine pond may prevent the need to treat the whole pond.

In many cases, tetracycline has proven effective in treating infections caused by Vibrio and Aeromonas, although other antibiotics are also available. It is important to follow the manufacturer’s instructions and remove activated carbon from filters before treatment. Medicated food may be used if the fish are still eating.

Aeromonas hydrophila and Bacterial Hemorrhagic Septicemia

Aeromonas hydrophila is a gram-negative motile rod that affects many freshwater species, usually under conditions of stress and overcrowding. The clinical signs and lesions vary, with the most common being hemorrhaging in the skin, fins, oral cavity, and muscles, alongside superficial ulceration of the skin.

Exophthalmus (bulging eyes) and ascites (fluid buildup in the abdomen) are frequently observed. Multifocal necrosis in organs such as the spleen, liver, kidney, and heart, with the presence of rod-shaped bacteria, can also be detected. Diagnosis is confirmed by culturing the organism from infected animals.

Aeromonas infections are transmitted through contaminated water or infected fish. These infections are common and cause significant issues in ponds and recirculating systems, where intensive farming practices increase stress on fish. In some cases, mortality rates can reach 100%.

Causes and Pathogenesis of Aeromonas Infections

Aeromonas hydrophila, A. sobria, A. caviae, and possibly other aeromonads are capable of producing disease in fish. These small, motile, gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria share certain biochemical characteristics, although their scientific names are under constant revision. Environmental strains tend to be less pathogenic than those isolated from diseased fish. The genetic diversity among aeromonad strains has made it difficult to develop effective vaccines.

Signs and Symptoms of Aeromonas Infections

Symptoms of Aeromonas infections vary and can be mistaken for other diseases. Infections may appear on the skin, internally as systemic disease (septicemia), or as a combination of both. Outbreaks can either be chronic, affecting a small number of fish, or acute, leading to high mortality rates.

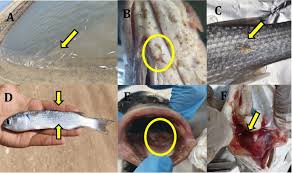

In unscaled fish like catfish, signs include frayed fins, red patches, and depigmented areas, which can develop into ulcers exposing the underlying muscle. In scaled fish like largemouth bass, small hemorrhages within scale pockets may expand into larger areas, resulting in scale loss and ulcer formation. Other external signs of infection include exophthalmia (popeye), abdominal swelling, and pale gills.

Fish affected with skin lesions may continue feeding despite severe ulceration. However, when the disease becomes septicemic, fish often stop eating and may be seen swimming near the surface or in shallow areas of the pond. Internally, organs may show hemorrhaging, necrosis, and other signs of tissue destruction. In severe cases, there may be cloudy or bloody fluid accumulation in the abdomen, and the gall bladder may contain excessive bile. Highly virulent strains of Aeromonas can cause sudden deaths without many visible signs of infection.

Read Also: 13 Medicinal Health Benefits of Chimaphila umbellata (Pipsissewa)

Treatment of Bacterial Diseases

Potassium permanganate (KMnO4) treatments, applied at 2 to 4 parts per million, can be effective for treating skin infections when fish are not feeding well. However, potassium permanganate is not officially approved by the Food and Drug Administration, although it is currently allowed. For systemic infections, medicated feeds containing antibiotics are essential for successful treatment. Early diagnosis is critical to ensure that fish can be treated before they stop feeding.

Fin Rot and Tail Rot in Fish

Fin and tail rot are common bacterial infections affecting both young and adult fish in hatcheries, nurseries, and grow-out ponds. These infections are highly contagious and can cause significant damage if left untreated. The primary cause of fin and tail rot in young fish is a mixed infection of Aeromonas hydrophila and Pseudomonas fluorescens.

These bacteria are short, motile, Gram-negative rods with polar flagella. The lesions resemble those caused by Aeromonas hydrophila and lead to hemorrhagic septicemia, resulting in hemorrhaging of the fins and tail, as well as skin ulceration. Most cases indicate underlying issues such as injury or poor environmental conditions.

Fin rot typically manifests as the erosion or shredding of the fish’s fins, beginning at the outer edges. The condition can be either bacterial or fungal in nature and is often triggered by poor water quality, inadequate diet, or physical injury.

Once diagnosed, fin rot is generally easy to treat, and fish fins can regenerate unless the infection progresses beyond the base of the fin. If the infection reaches this stage, it can become life-threatening as bacteria may enter the fish’s body.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Fungal fin rot usually presents with an even decay and a white edge on the affected fin, while bacterial fin rot produces jagged edges. In some cases, both fungal and bacterial infections can occur simultaneously, necessitating treatment for both conditions. Advanced cases may show redness and inflammation around the affected areas.

Diagnosis of fin rot is typically straightforward, and treatment varies based on the type of infection. For fungal infections, the affected area can be treated with an antiseptic like malachite green, while bacterial infections are usually treated with antibiotics in a quarantine tank. Using antibiotic-laced food is often preferred, as it minimizes the stress associated with quarantine. In severe cases, the rotted area may need to be surgically removed, though the fish must be sedated for the procedure.

Control Measures

Fin rot can be controlled through bath treatments using 1:2000 copper sulfate for two minutes, or by applying a concentrated copper sulfate solution directly to the affected fish. Preventing environmental stressors such as poor water quality, overcrowding, and injury is critical to avoid the recurrence of fin rot.

Gill and Fin Rot: Diagnosis and Pathology

Gill and fin rot are often caused by Myxobacteria of the genus Flexibacter, particularly Flexibacter columnaris, a common etiological agent in freshwater fish. These bacteria cause “saddleback” lesions and fin rot. In acute cases, gill lesions expand rapidly, leading to necrosis and often resulting in rapid death. Skin lesions, often localized to the head and back, appear white or yellow with reddish zones of hyperemia around the edges. These lesions are composed of bacterial cells and necrotic tissue covering hemorrhagic ulcers.

Histological examination reveals epidermal spongiosis and necrosis extending into the dermis. Chronic infections lead to extensive hyperplasia in the gills, causing the lamellae to fuse and proliferate mucus glands and chloride cells. Skin infections may result in fin erosion and ulceration at the skin folds.

Epizootiology of Myxobacterial Infections

Myxobacteria are opportunistic pathogens found in aquatic environments, typically colonizing damaged or ulcerated tissues, necrotic areas, or irritated mucus-secreting epithelium. Acute infections are often associated with mechanical damage to the skin or gills, such as during handling or sorting.

Poor environmental conditions, including low temperatures, high organic loads, ammonia, or nitrites, also contribute to the development of these infections. Chronic infections are more likely to occur in fish subjected to overcrowding, poor nutrition, or exposure to toxic substances.

Dropsy: Symptoms and Control

Dropsy, also known as ascites, is a condition characterized by a swollen body and protruding scales. It is not a disease in itself but rather a symptom of an underlying condition, often a bacterial infection caused by Aeromonas species. Infected fish may display lethargy and a lack of appetite. Dropsy results from a buildup of fluid in the fish’s body cavity, often due to kidney malfunction.

While Aeromonas is present in most aquatic environments, it typically becomes pathogenic in fish experiencing stress due to poor water quality or overcrowding. Infection may cause red streaks or sores on the fish’s body, though these symptoms are not always present. The internal fluid accumulation caused by dropsy can lead to severe health deterioration, often proving fatal if left untreated.

Control and Treatment

Treating dropsy is challenging, as it is often a secondary symptom of a more serious condition. Early-stage infections may be managed using broad-spectrum antibiotics and improving water quality. Neem leaf extracts and lime can be used to treat pond water, and fresh water changes can help control the disease.

Unfortunately, advanced cases of dropsy are usually fatal, as the internal damage caused by fluid buildup is often irreversible. Affected fish should be isolated in quarantine tanks and treated with antibacterial fish food and medications like Maracyn 2.

To prevent dropsy, it is essential to maintain optimal water quality through regular partial water changes (20-25%) and avoid overcrowding. Ensuring proper nutrition and stress management will also help reduce the likelihood of bacterial infections leading to dropsy.

Control of Infections by Facultative Pathogenic Bacteria

The most effective approach to controlling bacterial infections in fish is antibiotic therapy administered via medicated feeds. However, this is only feasible if the fish are still eating. Drug sensitivity tests should be conducted regularly to ensure the antibiotics used are effective.

Overuse of medicated feeds can lead to environmental harm, including damage to nitrification processes and primary production, and may promote antibiotic resistance among pathogens.

Vaccination has been considered as a potential solution for bacterial infections, and some research is ongoing. However, the effectiveness of vaccination in fish is still uncertain, and its economic viability remains a concern.

Immunization trials have shown varying degrees of success in protecting fish from specific bacterial challenges. For example, tilapia have shown increased antibody responses to various bacterial antigens following vaccination, but the durability and level of protection are still under investigation.

In Africa, strict controls on the importation of fish stocks are essential to prevent the introduction of bacterial infections such as Streptococcus and Pasteurella, which are prevalent in other regions.

Do you have any questions, suggestions, or contributions? If so, please feel free to use the comment box below to share your thoughts. We also encourage you to kindly share this information with others who might benefit from it. Since we can’t reach everyone at once, we truly appreciate your help in spreading the word. Thank you so much for your support and for sharing!

Read Also: How To Educate Yourself On Climate Change

Frequently Asked Questions

We will update this section soon.