Harvesting of crops generally is the task that constitutes the concluding stage of land cultivation. Harvesting includes several steps such as cutting in the case of cereal like maize, sorghum millet, gathering of the harvest, delivering for processing transportation of the processed material for storage or sale and storage.

You will need to understand that the primary stage in crop harvesting consists of two steps and these include the removal of the bulk plant material (i.e. picking the fruits and berries, cutting the grains and grasses, digging, the tubers and pulling the flax and subsequent producing.

The harvesting method used depends on the different crop species biological characteristics of the crop, climatic conditions, and technical equipment available.

Harvesting of Tropical Crops

Harvesting is an important component of crop production practices. The overall yield of a particular crop depends to some extent on the efficiency of a particular mode of harvesting (e.g. manual or mechanical).

Harvesting is done when a crop has reached physiological maturity or at the point of senescence when the leaves begin to change colour from green to yellow and drop (as in cereal grains and legumes, roots and tubers, bulbs) or the fruits showing signs of ripening).

However, if crops are harvested too early, the total yield may be affected due to immaturity.

Harvesting at the correct stage of maturity reduces greatly the level of spoilage of the crop. Where produce is to be held for any length of time, it is preferable to harvest at a mature but unripe stage.

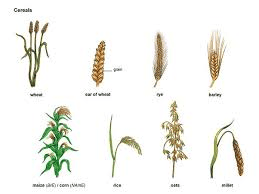

Harvesting of Cereal Crops

In the case of cereal grains, unripe crop contains a high level of moisture and deteriorate more rapidly than mature ones.

If matured grain crops are left on the fields much longer, the grains will be adversely affected due to the alternation between rain and sunshine, on one hand and that of dew at night and hot weather during the day.

Repeated wetting and drying cause certain grains such as long grained variety of rice paddy to crack open and shed their grains on the field.

Grain legumes split their pods and the seeds drop on the soil. Insect infestation occurs in the field at this time especially field to storage pests.

The timing of the harvest is very important, if maximum yields will be guaranteed with minimum loss.

Some matured grains like rice are harvested when they still contain some moisture, but, other types such as maize, sorghum, millet, e.g., are allowed to remain on the field to dry out sufficiently before harvesting.

This is only possible if the weather remains hot and sunny. All harvested grains should be free from cracks, insects and diseases for them to store well. One important point to note when cultivating any crop especially grains is timing planting.

This is important so that the time of maturity will coincide with the approaching dry season. For some grains like rice, the heads are harvested with a sickle and are allowed to dry for a few days outside and are then stacked.

Cracking which sometimes occurs may be due to rapid drying out in the field before harvesting. For sorghum and millet, the stems are cut low down, bundled together and stacked in the field.

Millet heads are cut about 15cm down the stem and are dried before storage. In some localities, the millet heads are arranged in bundles by tying the stalks together with the heads outside.

The bundles are rolled up ready for transport. Maize is harvested by plucking out the ears from the plaint when they are sufficiently dried on the field.

Grains may look dry at the time of harvest but, they still contain a lot of moisture which must be dried up before storage. For this reason, harvested grains are placed in containers or structures which allow a free flow of air between the grains.

This ensures that heat and moisture build up is reduced as the grain respires and at the same time discourages the growth of moulds and infestation by insects which affect the quality of stored grain.

1. Harvesting Methods for Rice

Manual Harvesting

In many countries, rice ears are cut by hand. A special knife is frequently used in many other countries.

For instance, rice is cut stem by stem with a knife, 10 cm below the panicle so as to leave straw in the field in amounts large enough to produce grazing for cattle. Nevertheless such practice is labour intensive.

To harvest denser varieties (500 stems/m2) instead of 100 stems/m2) a sickle is used mainly on a generally wetter produce. But work times remain high (100 to 200) man-hours per hectare for cutting and stocking.

Mechanized Harvesting

The first machines used were simple animal-drawn (horses in Europe, oxen in the tropics) or tractor-driven mowing machines fitted with a cutter bar. The improvements made on this equipment have first resulted in the development of swathers.

These drop the crop in a continuous windrow to the side of the machine making it easy to pick up the panicles and manually tie them into bundles.

The next step forward has been the reaper that forms unbound sheaves; and finally the reaper/binder which has a tying device to produce sheaves bound with a twine.

Read Also: 11 Unique Health Benefits of Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium)

However the supply, cost and quality of the twine are the main problems associated with the use of such equipment. The output of these machines varies between 4 and 10 hours per hectare, which is slow.

However, they may be usefully introduced into tropical rice growing areas, where hand harvesting results in great labour problems. In temperate countries they have been gradually replaced by combine harvesters.

Threshing Methods

After being harvested paddy bunches may be stacked on the plot. This in-field storage method results in a pre-drying of the rice ears before threshing, the purpose of which is to separate seeds from panicles.

Traditional Threshing

The traditional threshing of rice is generally made by hand: bunches of panicles are beaten against a hard element (e.g. a wooden bar, bamboo table or stone) or with a flail. The outputs are 10g to 30kg of grain per man-hour according to the variety of rice and the method applied.

Grain losses amount to 1-2%, or up to 4% when threshing is performed excessively late; some un- threshed grains can also be lost around the threshing area.

In many countries in Asia and Africa, the crop is threshed by being trodden underfoot (by humans or animals); the output is 30kg to 50kg of grain per man hour.

The same method, but using a vehicle (tractor or lorry) is also commonly applied. The vehicle is driven in circles over the paddy bunches as these are thrown on to the threshing area (15m to 20m in diameter around the stack).

The output is a few hundred kg per hour. This method results in some losses due to the grain being broken or buried in the earth.

Mechanized Threshing

From a historical viewpoint, threshing operations were mechanized earlier than harvesting methods, and were studied throughout the 18th century.

Two main types of stationary threshing machines have been developed.

The machines of Western design are known as ‘through-flow’ threshers because stalks and ears pass through the machine.

They consist of a threshing device with pegs, teeth or loops, and (in more complex models) a cleaning-winnowing mechanism based upon shakers, sieves and centrifugal fan.

Read Also: Traditional Methods of Crop Storage

The capacities of the models from European manufacturers or tropical countries (Nigeria, Brazil, India, etc.) range from 500 to 2000kg per hour.

In the 70s, IRRI developed an axial flow thresher which has been widely manufactured at local level. Such is the case in Thailand where several thousands of these units have been put into use. They are generally mounted on lorries and working about 500 hours per year.

More recently, a Dutch company (Votex) has developed a small mobile thresher provided with either one or two threshers. The machine has been widely adopted in many rice-growing areas. The simple design and work rates of these machines (about 500kg per hour) seem to meet the requirements of rural communities.

The ‘hold-on’ thresher of Japanese design is so-called because the bundles are held by a chain conveyor which carries them and presents only the panicles to the threshing cylinder, keeping the straw out. According to the condition of the crop, work rates can range between 300kg and 700kg per hour (Iseki model). The main disadvantage of these machines is their fragility

Combined Harvesting and Threshing Methods

Combine-harvesters, as the name implies, combine the actions of reaping and threshing. Either the ‘through-flow’ or the ‘hold-on’ principle of threshing may be employed, but the reaping action is basically the same.

The main difference is that combine-harvesters of the Western (‘through- flow’) type are equipped with a wide cutting bar (4-5m) while the working width of the Japanese (‘hold-on’) units is small (1m). According to the type of machine used, and specially to their working width, capacities range from 2 to 15 hours per hectare.

Such machines are being increasingly used in some tropical countries. In the Senegal river delta region, private contractors or farmers’ organizations have recently acquired combine harvesters, mainly of the Western type (Massey Ferguson, Laverda, etc.).

So, almost 40% of the Delta surface area is harvested with a pool of about 50 units. Between 200 and 300 hectares of rice are mechanically harvested. In this region the popularity of combine harvesters is high despite their poor suitability for some small-sized fields.

In Brazil, several manufacturers have adapted machines to rice growing conditions by substituting tracks for wheels; some machines are simple mobile threshers equipped with cutter bars.

In Thailand, local manufacturers have recently transformed the IRRI thresher into a combine harvester so as to reduce the labour requirement. The unit can harvest 5ha per day and seems to have been rapidly adopted.

Strippers

Because of their size, conventional harvesters and combine harvesters prove unsuitable for many rice growing areas with small family farm holdings. In response to this problem, research services, during the last ten years, have developed small-sized machines for harvesting the panicles without cutting the straw. Such machines are known as strippers.

In the United Kingdom, a rotor has been developed which is equipped with special teeth for strip-harvesting spikes or panicles. IRRI recently adopted this technology and has developed a 10 hp self-propelled ‘stripper gatherer’ with a capacity of about 0.1ha per hour.

However, the harvested grain has to be threshed and cleaned in a separate thresher. Since harvesting un- threshed produce results in frequent stoppages for emptying the machine, this constitutes the main drawback to the progress of the prototype.

In France, CIRAD-SAR has designed and developed a machine which strips panicles from the plants and threshes them in only one pass. The stripper has been specially designed for harvesting paddy rice on small plots.

The essential component is a wire looped in line with the direction of movement of the machine, which is mounted on a three-wheeled carriage and powered by a 9hp engine and with a 30 cm working width. The stripper capacity is about 1 ha per day.

2. The Harvesting Methods for Maize

In village farming systems the crop is often harvested by hand and cobs are stored in traditional structures. Quite often, the crop is left standing in the field long after the cobs have matured, so that the cobs may lose moisture and store more safely after harvest.

During this period the crop can suffer infestation by moulds and insects and be attacked by birds and rodents. To reduce such risks, an old practice (called “el doblado”) is sometimes applied in South and Central America.

This involves hand-bending the ears in the standing crop without removing them from the stalks. It helps mainly to prevent rainwater from entering the cobs, and also limits bird attacks; but, because of the high labour requirements involved, the practice is gradually falling into disuse.

Manual harvesting of maize does not require any specific tool; it simply involves removing the cob from the standing stalk. The work time averages 25 to 30 days per ha.

Traditionally, maize cobs are commonly stored in their un-husked form. To improve their drying, it is often recommended to remove the husks from the cobs.

Maize husking is usually a manual task carried out by groups of women. Some machine manufacturers (e.g. Bourgoin in France) have developed stationary maize huskers, such as the “Tonga” unit.

Mechanized Harvesting

The first mechanized harvester to detach ears of maize from the standing stalks, the ‘corn snapper’, was built in North America in the middle of the 19th century. This was followed by the development of ‘corn pickers’, which incorporated a mechanism for removing the husks from the harvested ears.

The first animal-drawn maize pickers were replaced by tractor-drawn units (l or 2 rows) and then tractor-mounted units (1 row). Finally came the development of self-propelled units capable of harvesting from up to 4 rows. A specific feature in maize harvesters is the header which leaves the stalks standing as it removes the ears.

The rates of work can vary from 2 hours per hectare with a 3-row self-propelled harvester to 5 hours per hectare with a tractor-drawn or -mounted single row unit. Generally speaking, harvest losses range from 3% to 5%, but they may be up to 10%-15% under adverse conditions.

Depending on the situation, a single-row harvester can be employed effectively on up to 20 hectares or more; but the use of a multi-row machine demands several tens of hectares to be economically effective.

Specially designed for harvesting maize as grain, the corn-sheller was initially a cornhusker in which the husking mechanism was replaced by a threshing one (usually of the axial type).

Corn- shellers are self-propelled machines of the 3 to 6-row type with capacities of 1 to 2 hours per hectare. The surface areas harvested during a 180-hour campaign range between 100ha (with a 3- row unit) and 200ha (with a 6-row one).

Another alternative consists of equipping a conventional combine with a number of headers corresponding to the machine horsepower. However, although widely used, such a method requires many adjustments to the threshing and cleaning mechanisms.

Threshing Methods

Shelling and Threshing

Traditional maize shelling is carried out as a manual operation: maize kernels are separated from the cob by pressing on the grains with the thumbs. According to the operator’s ability the work rate is about 10kg per hour.

Outputs up to 20kg per hour can be achieved with hand-held tools (wooden or slotted metal cylinders).

To increase output, small disk shellers such as those marketed by many manufacturers can be recommended. These are hand-driven or powered machines which commonly require 2 operators to obtain 150kg to 300kg per hour.

Another threshing method, sometimes applied in tropical countries, involves putting cobs in bags and beating them with sticks; outputs achieved prove attractive but bags deteriorate rapidly.

Motorized Threshing

Nowadays many small maize shellers equipped with a rotating cylinder of the peg or bar type, are available on the market.

Their output ranges between 500 and 2000kg per hour, and they may be driven from a tractor power take off or have their own engine; power requirements vary between 5 and 15hp according to the equipment involved.

3. Millet and Sorghum Harvesting

Manual Harvesting

In Africa, cereals constitute the staple food in the human diet. They are harvested almost exclusively by hand, with a knife after bending the taller stems to reach the spikes. Harvesting and removal from the field takes 10 to 20 days per hectare, according to yields.

Harvested ears are stored in traditional granaries while the straw is used as feed for cattle or for other purposes (e.g. thatching).

Gradual Mechanization of Threshing

Women separate the grain from the ears with a mortar and pestle, as it is needed for consumption or for marketing purpose. The threshed grain is cleaned by tossing it in the air using gourds or shallow baskets. The traditional method threshing is difficult and slow (10kg per woman-day).

Consequently, research has been conducted for some years on how to use mechanical method. The mechanical threshing of sorghum ears does not raise any special problems: conventional grain threshers can be used with some modifications; such as adjustment of the cylinder speed, size of the slots in the cleaning screens, etc.

On the other hand, the dense arrangement of spike lets on the rachis and the shape of millet ears (especially pearl millet), make their mechanical threshing excessively difficult.

Grain Cleaning

Threshing operations leave all kinds of trash mixed with the grain; they comprise both vegetable (e.g. foreign seeds or kernels, chaff, stalk, empty grains, etc.) and mineral materials (e.g. earth, stones, sand, metal particles, etc.), and can adversely affect subsequent storage and processing conditions.

The cleaning operation aims at removing as much trash as possible from the threshed grain. The simplest traditional cleaning method is winnowing, which uses the wind to remove light elements from the grain.

Mechanized Cleaning

The winnower was widely used in the past for on-farm cleaning of seed in Europe. It was either manually powered or motorized with capacities ranging from a few hundred kilogrammes to several tonnes per hour.

In Europe, with the use of combine harvesters and the development of centralized gathering, cereal winnowers have been progressively replaced by seed cleaners in the big storage centres.

These machines, also equipped with a system of vibrating sieves, are generally capable of very high outputs (several tens of tonnes per hour).

In developing countries, mechanizing the cleaning operation at village level has rarely been seen as a necessity, because of the lack of quality standards in grain trading. However, because of the current trend towards privatization of marketing networks, the demand for cleaning machines will probably increase.

The local manufacture and popularization of simple and easily portable equipment, such as winnowers or screen graders suited to cereal crops, need to be encouraged.

4. Harvesting of Tree Crops

Tree crops are harvested fresh at a point where full flavor and maturity are at equilibrium. Most fruits are picked when almost ripe and before they drop off the tree.

Those intended for long distance transportation or for export are picked when they have reached their full size and maturity but before softening. Immediately after harvest, fruits and vegetables show reduction in weight.

The flavor and palatability is also affected. For this reason, fruits need careful handling during harvesting and transport.

Tree crops such as citrus fruit is harvested by a mechanical picker by advancing a series of rotating disks into the three where the disk engage the fruit and pull it from the tree. The picker includes a housing having wheels for movement between rows of trees with a drive gearing assembly in the housing powered from a tractor.

Two disk assemblies, each comprising a pair of longitudinally space elongated support arms having inside ends supported on the housing, having outside ends supports supporting a shift extending longitudinally between the support arms.

The disks are arranged in pairs at longitudinally spaced intervals along the shaft with adjacent disks of each pair having oppositely facing surfaces. The arms can be raised and lowered to force the disk into the tree canopies from top to bottom of the trees.

5. Methods of Harvesting Citrus

Fruit crops such as citrus fruit is harvested by a mechanical picker by advancing a series of rotating disks into the three where the disk engage the fruit and pull it from the tree. The picker includes a housing having wheels for movement between rows of trees with a drive gearing assembly in the housing powered from a tractor.

Two disk assemblies, each comprising a pair of longitudinally spaced elongated support arms having inside ends supported on the housing, having outside ends supports supporting a shift extending longitudinally between the support arms.

The disks are arranged in pairs at longitudinally spaced intervals along the shaft with adjacent disks of each pair having oppositely facing surfaces. The arms can be raised and lowered to force the disk into the tree canopies from top to bottom of the trees.

6. Methods of Harvesting Coffee

The ripe cherries are harvested from coffee trees by using one of the following methods:

- Selective picking

- Stripping

- Mechanical harvesting

Selective Picking: Involves picking by hand only the ripe cherries from the tree and leaving behind unripe beans to be harvested at a later time.

This method is characterized by:

– being slow giving high quality of the fruit picked

– providing evenness of the harvest

– Relatively high costs

Stripping: Involves collecting the ripe and unripe cherries.

This is a procedure that can be performed by hand or machine, and involves stripping the plant of its fruit and leaves. The main characteristics of this process are:

– Greater speed

– Damage to plants

– Unevenness of the harvest

– Lower costs

Mechanical harvesting: Collecting the beans using a harvesting machine.

The method used depends on many factors such as time, cost effectiveness, availability of workers, and length of the harvest and difficulty of harvesting conditions, availability of water.

Coffee cherries are ready for harvest when they bright red, glossy, and firm.

7. Harvesting of Banana and Plantain

For banana and plantain, bunches are harvested at a stage of development which is assessed by the shape and angle of the fruit fingers.

Usually while the fruit fingers are immature, they are very angular but get filled out to a rounded or full shape when mature.

Bananas are harvested green and ripened artificially by placing them in a pit, surrounded and covered with banana leaves and soil, the ripening process is aided by lighting a fire near or around the hole containing the fruit or by placing the bananas on the hot ashes of a fire previously lit in the hole.

The fruit are left to ripen for 5 – 6 days and then removed, peeled and placed in a wooden trough made from a hollowed-out tree trunk.

For fruits such as melons, the condition of the stem is used as a basis to determine maturity.

8. Harvesting of Tuber and Root crops

Roots and tubers are harvested when the leaves begin to wilt and dry. These crops are not removed at once from the field but are harvested as at when needed over a period of time.

This is so because they store poorly and can easily deteriorate soon after harvests. Harvesting of roots, and tubers involves careful digging of the soil around the crop to avoid bruising and gently lifting up the root/tubers to present breakage (cutting).

In the case of cassava, the stem is cut some 15cm above the soil surface before uprooting the tubers. This enhances it storage changes.

However, root-crops and tubers generally present a number of problems during harvesting. They get damaged because they are heavy and of varying weights, and are poorly distributed in the soil.

In the case of yams, the tubers varying widely in shape and size and may be irregularly branched. This characteristic may encourage bruising during harvesting. It is important that roots and tubers are dug and handled carefully to avoid wounding.

When storage is desirable, the conditions should be such that they do not rot, sprout respire excessively or loss their food reserves. But at the same time, they must continue to live and undergo all the physiological processes that occur within living material.

In summary, the task of harvesting generally constitute the last stage of the cultivation and that includes the following steps as gathering, delivering, processing and transporting the processed for storage or sale.

Harvesting depends solely on the crop variety/species and its biological characteristics being it grain crops or trees, tubers and root crops. Crop maturity is also a determining factor to be considered before harvesting can commence.

Basically, there are two major means of harvesting and these include traditional method which is manual using hands while the other is the mechanical method that uses machines.

Understanding the primary stages in harvesting consist of the removal of the bulk plant material i.e. picking the fruits, cutting of the grains and grasses and digging of the tubers and root crops.

In achieving these, the method will either be traditionally which is manual and mechanically that involved the use machines for effectiveness and moderate in the amount lost.

Read Also: Water and Wastewater Management Complete Guide

Frequently Asked Questions

We will update this section soon.