Simple, low-cost, traditional food processing techniques are the bedrock of small-scale food processing enterprises that are crucial to rural development in West Africa. By generating employment opportunities in the rural areas, small scale food industries reduce rural-urban migration and the associated social problems.

They are vital to reducing post-harvest food losses and increasing food availability. Regrettably, rapid growth and development of small-scale food industries in West Africa are hampered by adoption of inefficient and inappropriate technologies, poor management, inadequate working capital, and limited access to banks and other financial institutions, high interest rates and low profit margins.

While a lot still needs to be done, some successes have been achieved in upgrading traditional West African food processing technologies including the mechanization of gari (fermented cassava meal) processing, the production of instant yam flour or flakes, the production of soy-ogi (a protein-enriched complementary food), the industrial production of dadawa (a fermented condiment).

Traditional Food Processing Technology

The capacity to preserve food is directly related to the level of technological development and the slow progress in upgrading traditional food processing and preservation techniques in West Africa contributes to food and nutrition insecurity in the sub-region.

Traditional technologies of food processing and preservation date back thousands of years and, unlike the electronics and other modern high technology industries, they long preceded any scientific understanding of their inherent nature and consequences.

Traditional foods and traditional food processing techniques form part of the culture of the people. Traditional food processing activities constitute a vital body of indigenous knowledge handed down from parent to child over several generation. Unfortunately, this vital body of indigenous knowledge is often undervalued.

Regrettably, some of the traditional food products and food processing practices of West Africa have undoubtedly been lost over the years and the sub-region is the poorer for it.

Those that the sub-region is fortunate to retain today have not only survived the test of time but are more appropriate to the level of technological development and the social and economic conditions of West African countries.

Indeed, simple, low-cost, traditional food processing techniques are the bedrock of small-scale food processing enterprises in West Africa and their contributions to the economy are enormous.

Table: Objectives and main features of traditional West African food processing techniques

Technique/operationsobjectivesMean features/limitations1. Preliminary/postharvest operations: threshingTo detach grain kernels from the panicle.Carried out by trampling on the grain or beating it with sticks. Labour-intensive, inefficient, low capacity.WinnowingTo separate the chaff from the grain.Done by throwing the grain into the air. Labour intensive, low capacity, inefficient.

casingwith pestle. Labour-intensive, low capacity excessive grain breakage.PeelingTo separate the peel or skin from the edible pulp.Manual peeling with knives or similar objects. Labour-intensive, low capacity, loss of edible tissue.2. Milling (e.g. corn)

Dry millingTo separate the bran and germ from endospermCarried out by pounding in a mortar with pestle or grinding with stone. Laborious, inefficient, limited capacity.Wet millingTo recover mainly starch in the production of fermented foods e.g. ogi.Carried out by pounding or grinding after steeping. Laborious, limited capacity, high protein losses, poor quality product.3. Heat processing

RoastingTo impart desirable sensory qualities, enhance palatability, reduce anti-nutritional factors.Peanuts are roasted by stirring in hot sand in a flat-bottom frying pot over a hot flame. Laborious, limited capacity.Cooking (e.g. wara)To contract curd and facilitate whey expulsion, reduce microbial load, inactivate vegetable rennet, impart desirable sensory qualities.Loose curd pieces are cooked in a pot over wood fire. Limited capacity.

quality product.BlanchingTo inactivate plant enzymes and minimize oxidative changes leading to deterioration in sensory and nutritional qualities, e.g. enzymatic browning.Slices (e.g. yam for elubo production) are heated in hot water in a pot for various durations. Limited capacity, poor quality product.4. Drying

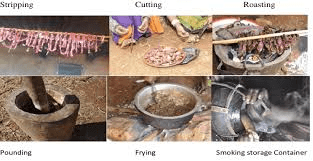

Shallow layer sun dryingTo reduce moisture content and extend shelf life.Product is spread in a thin layer in the open (roadside, rooftop, packed earth etc.). Labour intensive, requires considerable space, moisture too high for long- term stability, poor quality.Smoke drying (e.g. banda)To impart desirable sensory qualities, reduce moisture content and extend shelf life.Meat chunks after boiling are exposed to smoke in earthen kiln or drum. Limited capacity, poor quality product.5. FermentationTo extend shelf life, inhibit spoilage and pathogenic microorganisms, impart desirable sensory qualities, improve nutritional value or digestibility.Natural fermentation with microbial flora selection by means of substrate composition and back-slopping. Limited capacity, variable quality.Source: International Union of Food Science & Technology (2008)

Traditional Fermentation

Fermentation is one of the oldest and most important traditional food processing and preservation techniques. Food fermentations involve the use of microorganisms and enzymes for the production of foods with distinct quality attributes that are quite different from the original agricultural raw material.

The conversion of cassava (Manihot esculenta, Crantz syn. ManihotutilissimaPohl) to gari illustrates the importance of traditional fermentations. Cassava is native to South America but was introduced to West Africa in the late 16th century where it is now an important staple in Nigeria, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea, Senegal and Cameroon.

Nigeria is one of the leading producers of cassava in the world with an annual production of 35-40 million metric tons. Over 40 varieties of cassava are grown in Nigeria and cassava is the most important dietary staple in the country accounting for over 20% of all food crops consumed in Nigeria.

Read Also : Fish Farming Technique and Hatchery Management

Cassava tubers are rich in starch (20-30%) and, with the possible exception of sugar cane, cassava is considered the highest producer of carbohydrates among crop plants. Despite its vast potential, the presence of two cyanogenic glucosides, linamarin (accounting for 93%of the total content) and lotaustralin or methyl linamarin, that on hydrolysis by the enzyme linamarase release toxic HCN, is the most important problem limiting cassava utilization.

Generally cassava contains 10-500 mg HCN/kg of root depending on the variety, although much higher levels, exceeding 1000 mg HCN/kg, may be present in unusual cases. Cassava varieties are frequently described as sweet or bitter.

Sweet cassava varieties are low in cyanogens with most of the cyanogens present in the peels. Bitter cassava varieties are high in cyanogens that tend to be evenly distributed throughout the roots.

Environmental (soil, moisture, temperature) and other factors also influence the cyanide content of cassava. Low rainfall or drought increases cyanide levels in cassava roots due to water stress on the plant.

Apart from acute toxicity that may result in death, consumption of sub-lethal doses of cyanide from cassava products over long periods of time results in chronic cyanide toxicity that increases the prevalence of goiter and cretinism in iodine-deficient areas.

Symptoms of cyanide poisoning from consumption of cassava with high levels of cyanogens include vomiting, stomach pains, dizziness, headache, weakness and diarrhea.

Chronic cyanide toxicity is also associated with several pathological conditions including konzo, an irreversible paralysis of the legs reported in eastern, central and southern Africa, and tropical ataxic neuropathy, reported in West Africa, characterized by lesions of the skin, mucous membranes, optic and auditory nerves, spinal cord and peripheral nerves and other symptoms.

Without the benefits of modern science, a process for detoxifying cassava roots by converting potentially toxic roots into gari was developed, presumably empirically, in West Africa. The process involves fermenting cassava pulp from peeled, grated roots in cloth bags and after dewatering, the mash is sifted and fried.

During fermentation, endogenous linamarase present in cassava roots hydrolyze linamarin and lotaustralin releasing HCN. Crushing of the tubers exposes the cyanogens which are located in the cell vacuole to the enzyme which is located on the outer cell membrane, facilitating their hydrolysis.

Most of the cyanide in cassava tubers is eliminated during the peeling, pressing and frying operations. Processing cassava roots into gari is the most effective traditional means of reducing cyanide content to a safe level by WHO standards of 10 ppm, and is more effective than heap fermentation and sun drying, commonly used in eastern and southern Africa.

Apart from gari there is a vast array of traditional fermented foods produced in Nigeria and other West African countries. These include staple foods such as fufu, lafun and ogi; condiments such as iru (dawadawa), ogiri (ogili) and ugba (ukpaka); alcoholic beverages such as burukutu (pito or otika), shekete and agadagidi; and the traditional fermented milks and cheese.

Lactic acid bacteria and yeasts are responsible for most of these fermentations. The fermentation processes for these products constitute a vital body of indigenous knowledge used for food preservation, acquired by observations and experience, and passed on from generation to generation.

Dadawa Fermentation

Dadawa or iru is the most important food condiment in Nigeria and many countries of West andCentral Africa (21). It is made by fermenting the seeds of the African locust bean. The seeds are rich infat (39-47%) and protein (31-40%) and dadawa contributes significantly to the intake of energy, protein and vitamins, especially riboflavin, in many countries of West and Central Africa.

For the production of dadawa, African locust bean seeds are first boiled for 12-15 hr or until they are tender. This is followed by dehulling by gentle pounding in a mortar or by rubbing the seeds between the palms or trampling under foot. Sand or other abrasive agents may be added to facilitate dehulling.

The dehulled seeds are boiled for 30 min to 2 hr, molded into small balls and wrapped in banana leaves. A softening agent called kuru containing sunflower seed and trona or kaun‘ (sodium sesquicarbonate) may be added during this second boiling to aid softening of the cotyledons.

The seed balls are then covered with additional banana leaves or placed in raffia mats and allowed to ferment for 2-3 days covered with jute bags. Alternatively, the dehulled seeds, after boiling, are spread hot on wide calabash trays in layers of about 10 cm deep, wrapped with jute bags and allowed to ferment for about 36 hrs.

The fermented product is salted, molded into various shapes and dried. The main microorganisms involved in dadawa fermentation are Bacillus subtilis and Bacilluslicheniformis and one of the most important biochemical changes that occurs during fermentation is the extensive hydrolysis of the proteins of the African locust bean.

Other biochemical changes that occur during dadawa fermentation include the hydrolysis of indigestible oligosaccharides present in African locust bean, notably stachyose and raffinose, to simple sugars by α- and β-galactosidases, the synthesis of B-vitamins (thiamin and riboflavin) and the reduction of antinutritional factors (oxalate and phytate) and vitamin C.

An improved process for industrial production of dadawa involves dehulling African locust bean with a burr (disc) mill, cooking in a pressure retort for 1 hr, inoculating with Bacillus subtilis starter culture, drying the fermented beans and milling into a powder.

Cadbury Nigeria Plc in 1991 introduced cubed dawadawa but the product failed to make the desired market impact and was withdrawn. It would appear that consumers preferred the granular product to the cubed product.

Importance of Fermentation

Apart from detoxification by the elimination of naturally-occurring nutritional stress factors, other benefits of traditional fermentations include reduction of mycotoxins such as aflatoxins as in ogi processing the conversion of otherwise inedible plant items such as African locust bean (ParkiabiglobosaJacq) and African oil bean (PentaclethramacrophyllaBenth) to foods, i.e. iru and ugba respectively, by extensive hydrolysis of their indigestible components by microbial enzymes.

Fermentation improves the flavor and texture of raw agricultural produce, imparting a desirable sour taste to many foods, such as gari and ogi, and leading to the production of distinct flavor components characteristic of many fermented foods.

Fermentation may lead to significant improvement in the nutritional quality of foods by increasing the digestibility of proteins through hydrolysis of proteins to amino acids, increasing bio-availability of minerals such as calcium, phosphorus, zinc and iron through hydrolysis of complexing agents such as phytate and oxalate, and increasing nutrient levels, especially B-vitamins, through microbial synthesis.

Production of Complementary Foods

It is generally agreed that breast milk is adequate both in quantity and quality to meet the nutrient and energy requirements of the infant up to the age of four to six months. Beyond this period, complementary or weaning foods are required to supplement the mother‘s breast milk.

The weaning period is the most critical in the life of infants and preschool children, with serious consequences for growth, resistance to diseases, intellectual development and survival if the child‘s nutritional needs are not met.

Unfortunately, in West Africa and other parts of Africa, traditional complementary foods are made from cereals, starchy roots and tubers that provide mainly carbohydrates and low quality protein. These complementary foods exemplified by ogi are the leading cause of protein-energy malnutrition in infants and preschool children in Africa.

African infants experience a slower growth rate and weight gain during the weaning period than during breastfeeding due primarily to the poor nutritional qualities of traditional African complementary foods such as ogi.

Apart from their poor nutritional qualities, traditional African cereal-based gruels used as complementary foods have high hot paste viscosity and require considerable dilution before feeding; a factor that further reduces energy and nutrient density.

Although nutritious and safe complementary foods produced by food multinationals are available in West African countries, they are far too expensive for most families.

The economic situation in these countries necessitates the adoption of simple, inexpensive processing techniques that result in quality improvement and that can be carried out at household and community levels for the production of nutritious, safe and affordable complementary foods.

Complementary Foods from Cereal-Legume Blends

As cereals are generally low in protein and are limiting in some essential amino acids, notably lysine and tryptophan, supplementation of cereals with locally available legumes that are high in protein and lysine, although often limiting in sulfur amino acids, increases protein content of cereal-legume blends and their protein quality through mutual complementation of their individual amino acids.

This principle has been utilized in the production of high protein-energy complementary foods from locally available cereals and legumes. Community-based weaning food production using 4:1 ratio of locally available cereals and legumes have proved successful in many African countries.

Weanimix‘, a weaning food made from a cereal-legume blend, developed by the Nutrition Division of the Ministry of Health in Ghana was introduced on a large scale in the country in 1981.

To promote the production of weaning foods from locally available cereals and legumes at the household level, grinding mills were provided to rural women groups in Ghana with UNICEF assistance.

Although legume supplementation increases protein content and protein quality of cereal-legume blends, the types of cereal and legume involved as well as the blending ratios are critical. Increasing legume concentration in the blend generally increases the protein score until a new limiting amino acid is imposed.

Using a blend quality prediction procedure based on the amino acid scores of mixtures of cereals and legumes, the relative performance of maize, millet and sorghum supplemented with cowpea, groundnut, pigeon pea, soybean and winged bean in various weaning formulations has been estimated.

Mixtures of cereals with groundnut produced the poorest quality blends due to the relative inadequacy of groundnut protein in complementing cereal amino acids. Soybean and winged bean produced the best quality blends with cereals, followed by cowpea and pigeon pea in that order.

Production of Instant Yam Flour

Yam, possibly the oldest cultivated food plant inWest Africa, is of major importance to the economy of the sub-region that accounts for the bulk of world production of the crop. By far the most important product derived from white yam (Dioscorea rotundata Poir) is fufu or pounded yam, popular throughout West Africa.

Traditionally, pounded yam is prepared by boiling peeled yam pieces and pounding using a wooden mortar and pestle until a somewhat glutinous dough is obtained.

Arising from the need to have a convenience food and reduce the drudgery associated with the preparation of pounded yam, various brands of instant yam flour are now available in West Africa since the introduction of poundo yam, which is no longer in the market, by Cadbury Nigeria Ltd in the 1970s.

Instant yam, on addition of hot water and stirring, reconstitutes into dough with smooth consistency similar to pounded yam. The product is so popular that considerable quantities are exported to other parts of the world, especially Europe and North America, where there are sizable African populations.

Commonly, instant yam flour is produced by sulfiting peeled yam pieces, followed by steaming, drying, milling and packaging in polyethylene bags. Instant yam flour can also be produced by drum drying cooked, mashed yam and milling the resultant flakes into a powder using a process similar to that used for production of dehydrated mashed potato.

Table: Some Traditional Nigerian Fermented Foods

Fermented foodRaw materialsMicroorganism involvedUsesGariCassava pulpLeuconostoc spp. Lactobacillus spp. Streptococcusspp. GeotrichumcandidumMain MealFufuWhole cassava rootsLactobacillusspp. Leuconostocspp.Main mealLafunCassava chipsLeuconostoc spp. Lactobacillus spp. Corynebacteriumspp. CandidatropicalisMain mealOgiMaize, sorghum and milletLactobacillusplantarumStreptococcus lactisSaccharomycescerevisiaeRodotorulaspp. Candidamycoderma DebaryomyceshanseniiBreakfast cereal, weaning foodIru (Dawadawa)African locust bean (Parkiabiglobosa) Soya beanBacillussubtilis B.licheniformisCondimentOgiri (Ogili)Melon seed (Citrullusvulgaris), Fluted pumpkin (Telfairiaoccidentalis), Castor oil seed (Ricinuscommunis)Bacillus spp.Escherichia spp.Pediococcusspp.CondimentKpayeProsopsisafricana (algarroba or mesquiteBacillus subtilisBacilluslicheniformis BacilluspumilusCondimentUgba (Ukpaka)African oil bean (Pentaclethramacrophylla)Bacillus licheniformisMicrococcusspp. Staphylococcusspp.Delicacy usually consumed with stock fish or dried fish

Lactic acid bacteria Acetic acid bacteria

Burukutu/Pito/OtikaSorghum Millet &maizeSaccharomycesspp. Lactic acid bacteriaAlcoholic drinkSheketeMaizeSaccharomycesspp.Alcoholic drinkAgadagidiPlantainSaccharomycesspp.Alcoholic drink

Traditional method of Flour Production

Traditionally, cereal grains are processed either in the dry or wet form to make various products. Maize, sorghum, rice and wheat are de-hulled first by pounding and then by winnowing. The crushed grain is then ground on large grinding stones to produce a dry flour.

Whole grain is sometimes moistened before grinding to produce whole grain flour. This process is tedious and time consuming and recovery rate is about 50 to 60% which is very low. The product obtained contains about 30% moisture making it to be unstable.

The instability of the flour is improved by repeated pounding. Soaked cereal grains may also be ground into meals which are mixed with water to form dough whole cereal meals produced by grinding are not passed through a sieve to remove any part of the cereal. They are 100% extracts.

Brown Flours

These are produced by just drying the cereal grains, which are then roasted and ground into brown flours with a pleasant flavor. These flours are used in making breakfast porridges, cooked paste products, in soups as thickening agents in plantain products or as beverages by mixing in ginger solution with sugar added.

Traditional Boiling of Roots and Tubers

In traditional food preparation, sweet cassava, cocoyam, sweet potato and yam are wasted, peeled and covered with cold water for boiling-either alone or in combinations seasonings are added to enrich its palatability and flavour.

Fufu Processing

Boiled roots and tubers are pounded in a shallow wooden mortar with a fufu stick or a wooden pestle to produce a paste commonly call fufu. In order to produce good quality fufu, the cut roots or tubers are cooked until they are just done, with the starch granules partially gelatinized over cooking causes too much gelatinization and the product does not form fufu. The pieces are crushed, little by little, with the fufu pestle.

This prevents lumpiness in the finished product. The crushing continues until all pieces are completely crushed before the actual pounding begins. The pounding mass is moistened with some cold water and is turned over by hand between beatings.

The beating causes the starch granules to break down and imbibe water causing the mass to become soft, sticky and elastic. At the desired level of stickiness and softness, the product is shaped into forms and served with thin or thick soups.

Fufu is either made with one type of root or tuber such as cassava, yam, or cocoyam or is made in combination. Sweet potato is never used to make fufu, since it is too sweet and does not become sticky or elastic when pounded.

Preparation of Fried and Roasted Roots and Tuber Snacks

Pared yam, cocoyam and potatoes are cut up, salted and deep fat fried to make fried products. The snacks are sold as ready-to-eat or convenience foods. The curt pieces are also grilled or roasted on an open fire as ready-to-eat foods.

Cocoyam, irish potato and green plantain can also be thinly sliced, fried in oil and salted to make crisps which are packaged and sealed in plastic bags as snacks. Note that yams are not usually used for crisps because they become bitter when fried to crispiness.

Processing of Cassava into Garri

The commercial and traditional methods of processing cassava into gari are guided by the same basic principles. The fresh tuber is peeled, washed and grated to produce pulp. The pulp is then collected and packed in a hessian bag.

This bag is pressed down either mechanically or in traditional form by use of stones or other heavy materials for about 3 days during this process, moisture is lost and some hydrogen cyanide or prussic acid is eliminated. Also a fermentation process eats in with the liberation of more hydrogen cyanide.

Two stages of fermentation reaction are identified in grated cassava mash. The first stage involves the attack of starch granules by some cassava bacteria which produce acids, causing a reaction with the poisonous compounds to form gases which are liberated within 24 hours of fomentation.

The second stage occurs when sufficient organic acids including lactic acid have been produced in the mash. Fermentation by yeasts then occurs to form compounds which give the characteristics taste and flavor to fermented cassava dough products, especially the aroma in gari or fermented roasted cassava meal.

The pulp is sifted to remove the coarse fibres and leave the starch or garri which is later heat dried (fried) with constant stirring. Any hydrogen cyanide left behind is virtually destroyed.

To produce the yellow type of garri, a little palm oil is added during frying to give the characteristic colour. The finished product (gari) has a swelling capacity of about three times its weight when cold water is added. In the dried form it can store for some time.

Processing of Fruits and Vegetables

Nigeria is richly endowed with a wide range of indigenous fruits and vegetables which play important roles in nutrition and healthy body development. They are also available sources of raw materials for growing Agro-allied industries.

Due to inadequate nutritional education, limited utilization potentials, seasonal variability, the perishable nature of the foods, inadequate preservation methods, and the consumption habits of the people, the great potentials of these foods have not been realized.

The result is under exploitation and wasting away of the abundant fruits and vegetables in all ecological zones of the country.

Fruits are classified as the fleshy edible products of a woody or perennial plant which are closely associated with flower (e.g. mango, pineapple, guava, banana, avocado pear, apple, grape, citrus, plantain, passion fruits Saturn/sweet sops, etc).

Vegetables on the other hand are the shrubs or herbaceous annual or which may be the leaves, shrubs, roots, flowers, seeds, fruits or inflorescence of the plant.

In Nigeria for instance, most of the commonly used vegetables are the leaves, seeds fruits and roots which are the succulent plants parts catch as supplementary foods, side dishes (raw) or as soup with condiments along with other main staple dishes (e.g. spinach, lettuce, cabbage, cauliflower, pumpkin, bitter leaf, amaranthus, onions, tomatoes, okra, pepper, melons, garlic, peas etc.).

Fruits and vegetables are perishable food and so require some form of processing for longer storage. The processing of fruits and vegetable has been carried out in almost every home in the country but the storage life of most of the processed foods does not offer encouragement for commercial exploitation.

Read Also: Principles of Crop Storage and Methods of Storage of Crops

There are very few factors like Lafia Canning Factory in Oyo State and the Vegetable and Fruit Processing Company Ltd in Borno State that operate exclusively on fruit and vegetable processing in Nigeria.

Other cottage industries like Takog Food Processing Company and Tella Fruit Juice Industries both at Ibadan, Oyo State, that process fruits and vegetables on a small scale for limited circulation.

The vegru company in Bauchi process fruit into juices and tomatoes into puree. The two major firms marketing fruit squashes, Lever Brother Nigeria Ltd and the Nigeria Bottling Company Ltd, produce entirely from imported concentrates.

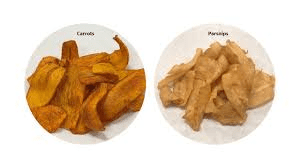

There are several methods used in processing fruits and vegetables to facilitate their storage with a longer shelf life. This makes them available during out-of-season periods. These methods include dehydration, canning, processing with sugar, fermentation and picking.

Dehydration

Fruits and vegetables are having tissues with cellulose wall which is semi-permeable. The cellulose wall is killed by either heating or freezing which allows the food material to lose water but retaining the nutrients in them. The deliberate removal of water from food products before marketing is referred to as dehydration drying or evaporation.

After the removal of water, the products remains in a liquid or fluid state, and this is termed evaporation. When the end product is in solid form, the material is said to have been dried or dehydrated.

The primary objective in removing water from any food material is to reduce its bulk, so that it can be economically handled, transported, and distributed.

The objective is to improve its keeping quality by reducing the moisture level. Fruits and vegetables have a high moisture content and are highly perishable. If moisture is removed, these food material can be preserved over a long period with minimal microbial attack.

Fruits and vegetables are heat-sensitive and therefore present special problems when drying. Dehydration has to be carried out under carefully controlled conditions. Prolonged heat treatment results in a loss of flavor, a decrease in nutritional quality, vitamin losses, and a marked decline in the acceptability of the product. Successful dehydration therefore involved minimal heat treatment as well as careful handling.

When properly done, drying can preserve taste, concentrate flavors and protect nutritive values. Drying is inexpensive, in energy terms and dried products are also economical in their storage requirements.

A combination of warmth, low R Humidity and moving air will dry any product. Dry air circulating around moist food collects some of the moisture from the food. With an air flow to carry away the moisture-laden air while allowing dry air in, the drying continues until an equilibrium or a balance is reached.

Although heat is needed for drying, a low R H. and air movement are more important. Too low temperature and or too high R. H may cause prolonged drying period which may result in food spoilage.

Conversely, a high temperature with a low humidity cause ―case hardening‖ (a situation when the outside layer of the food fries very quickly and hardens, so locking moisture into the product and casing spoilage problems).

Preparing Fruits and Vegetables for Drying

Fruits and vegetables to be dried must of top quality. Duping will preserve most of the original flavor but will not improve food quality. Fruits and vegetables are thoroughly washed preferably in cold water.

Cold water helps to preserve freshness soaking fruits and vegetables in water is not recommended, since vitamins are leached out. The food absorbs moisture, which makes drying more difficult. The washed produce is trimmed, peeled if necessary and cut up into pieces.

Food to be dried is cut into various shapes, helves, cubes, slices and strips. The thinner and smaller the pieces, the quicker they dry. It is necessary that they are as uniformly cut as possible to allow for uniform drying and retaining the nutrients in them. The deliberate removal of water from food products before marketing is referred to as dehydration drying or evaporation.

After the removal of water, the products remains in a liquid or fluid state, and this is termed evaporation. When the end product is in solid form, the material is said to have been dried or dehydrated.

The primary objective in removing water from any food material is to reduce its bulk, so that it can be economically handled, transported, and distributed.

The objective is to improve its keeping quality by reducing the moisture level. Fruits and vegetables have a high moisture content and are highly perishable. If moisture is removed, these food material can be preserved over a long period with minimal microbial attack.

Fruits and vegetables are heat-sensitive and therefore present special problems when drying. Dehydration has to be carried out under carefully controlled conditions. Prolonged heat treatment results in a loss of flavor, a decrease in nutritional quality, vitamin losses, and a marked decline in the acceptability of the product. Successful dehydration therefore involved minimal heat treatment as well as careful handling.

When properly done, drying can preserve taste, concentrate flavors and protect nutritive values. Drying is inexpensive, in energy terms and dried products are also economical in their storage requirements.

A combination of warmth, low R Humidity and moving air will dry any product. Dry air circulating around moist food collects some of the moisture from the food. With an air flow to carry away the moisture-laden air while allowing dry air in, the drying continues until an equilibrium or a balance is reached.

Although heat is needed for drying, a low R H. and air movement are more important. Too low temperature and or too high R. H may cause prolonged drying period which may result in food spoilage.

Conversely, a high temperature with a low humidity cause ―case hardening‖ (a situation when the outside layer of the food fries very quickly and hardens, so locking moisture into the product and casing spoilage problems)

Mango Processing

Ripe mature mango is most suitable for juice production. The fruits are peeled manually and collected into the crushing machine which grinds them into a very fine blend.

A considerable amount of water is added to the blend in the container, thoroughly mixed and siphoned into a pre-heater which preheats it to 15 – 20oC, then to the juice extractor which separates the pulp from the juice.

The juice is then clarified to separate out sediments still present in the juice. The juice is pasteurized before filling into sterilized cans using automatic filling machine.

The filled cans are conveyed through the conveyor belt to the automatic sewing machine after which they are immersed in boiling water for adequate time period (20 to 30 minutes) for complete sterilization. After sterilization, the cans are pre-cooled, cooled finally and packed.

Plantain processing

Plantain is processed into flour for longer preservation. The flour could be used for the production of baked goods like bread, cake and biscuit. Other food products which could be produced from plantain in a cottage industry are chips and dodo.

Plantain flour production is usually carried out as a means of preservation, price stability and for easy transportation to other parts of the country where plantain is not grown.

Read Also : How to treat Ruminant Animal Diseases

Until recently, the production has been carried out on very small-scale by individual households who process into flour the surplus plantain fruits which could not be consumed or sold fresh. Plantain flour is produced by drying, milling and sieving to coffee beans, kola nuts, tobacco leaves etc.

Crop produce are subject to varying degrees of post-harvest loss. Post-harvest loss is defined as any change in the availability, edibility (where applicable), wholesomeness or quality of produce, produce that reduces its value to humans which dares, place during the period between maturity of the crop and the time of its final consumption or utilization.

In conclusion, the critical role that food science and technology plays in national development cannot be overemphasized in West African countries where high post-harvest losses, arising largely from limited food preservation capacity, is a major factor constraining food and nutrition security.

Seasonal food shortages and nutritional deficiency diseases are still a major concern. While the large food multinationals play a unique role in promoting industrial development in West Africa through employment generation, value-added processing and training of skilled manpower, their impact is felt greatest in the urban areas.

Small-scale food industries that involve lower capital investment and that rely on traditional food processing technologies are crucial to rural development in West Africa. By generating employment opportunities in the rural areas, small scale food industries reduce rural urban migration and the associated social problems.

They are vital to reducing post-harvest food losses and increasing food availability. While a lot still has to be done in upgrading traditional West African food processing technologies, some successes have been achieved including the mechanization of gari processing, the production of instant yam flour, the production of soy ogi, the industrial production of dadawa.

Traditional food processing activities constitute a vital body of indigenous knowledge handed down from parent to child over several generations. Unfortunately, this vital body of indigenous knowledge is often undervalued.

Regrettably, some of the traditional food products and food processing practices of West Africa have undoubtedly been lost over the years and the sub- region is the poorer for it.

Those that the sub-region is fortunate to retain today have not only survived the test of time but are more appropriate to the level of technological development and the social and economic conditions of West African countries.

Indeed, simple, low-cost, traditional food processing techniques are the bedrock of small-scale food processing enterprises in West Africa and their contributions to the economy are enormous. Simple, low-cost, traditional food processing techniques are the bedrock of small-scale food processing enterprises in West Africa and their contributions to the economy are enormous.

Traditional foods and traditional food processing techniques form part of the culture of the people. Traditional food processing activities constitute a vital body of indigenous knowledge handed down from parent to child over several generations.

Unfortunately, this vital body of indigenous knowledge is often undervalued. Regrettably, some of the traditional food products and food processing practices of West Africa have undoubtedly been lost over the years and the sub-region is the poorer for it.

Those that the sub-region is fortunate to retain today have not only survived the test of time and more appropriate to the level of technological development and the social and economic conditions of West African countries.

Read Also: How to Reduce the Amount of Wastes Produced

Frequently Asked Questions

We will update this section soon.