As a beginner, there are most times many questions you may wish to ask concerning your ruminant animals and am sure that a question like this one: how do I know when my ruminants are suffering from worm infestation must be one of them.

Secondly, you may also wish to know the signs and symptoms and how to go about their treatment. Don’t worry as we are going to discuss all that below:

There are many signs that can indicate worm infestation in ruminant animals and these include: Loss of weight due to the competition between the animals and the worms for digested feeds, the animals begin to lose weight, the animals may lose appetite, there could be diarrhea and worms may be seen on their feaces.

There are times when worm infestation may cause the animals to cough. Any or all of these signs may make worm infestation a suspect among your ruminant animals. However, these signs are not confirmatory of the condition, further steps must still be taken to confirm.

Now let us go to how often your ruminant animals should be treated against worm infestation and which drug is best for you to use: As a routine, it is good that you deworm your animals at least once in three months or as recommended by your consultant depending on the location of your farm.

Apart from routine deworming, it may be recommended any time signs of worm infestation are seen on the animals. As for the ideal drugs, there are countless number of dewormers that can be used with good results. Some of them are liquid, some bolus while others are in powdery form. The choice of the drugs should depend on your consultant’s recommendation.

Livestock Animals Parasites

Parasites are a major cause of disease and production loss in livestock, frequently causing significant economic loss and impacting on animal welfare. In addition to the impact on animal health and production, control measures are costly and often time-consuming. A major concern is the development of resistance by worms, lice and blowflies to many of the chemicals used to control them.

Planned preventative programs are necessary to minimise the risks of parasitic disease outbreaks and sub-clinical (invisible) losses of animal production, and to ensure the most efficient use of control chemicals.

Integrated parasite management programs aim to provide optimal parasite control for the minimal use of chemicals by integrating pre-emptive treatments, parasite monitoring schedules and non-chemical strategies such as nutrition, genetics and pasture management.

Internal parasites of ruminants

Parasites

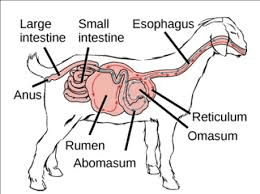

A parasite lives in or on another animal and feeds on it. All animals and humans can become infected with parasites. Ruminants can be infected with several types of worms.

Types of parasites

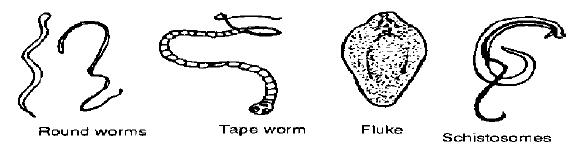

- Roundworms are small, often white in color, and look like threads. Different roundworms are found in all parts of the gut and the lungs.

- Tapeworms are long, and flat and look like white ribbons. They consist of many segments and live in the intestine.

- Flukes are flat and leaf-like, they live in the liver. Schistosomes are small and worm-like, both infect animals kept on wet, marshy ground as their eggs develop in water.

- The roundworms, flukes and schistosomes lay eggs which pass out of the animal in the dung onto the pasture.

- Tapeworms produce eggs in the segments which break off and pass out in the dung. Animals become infected when they graze the pasture.

The effect of parasites on the animals

- Parasites feed on the food in the gut and on the blood of the host.

- The animal becomes weak and loses weight or does not gain weight. It can develop diarrhea, which in sheep makes the wool wet and attracts flies.

- Eventually the host becomes so weak that it dies. Young animals are especially affected by parasites.

Animals becoming infected with parasites

Read Also: How to treat Ruminant Animal Diseases

Control of parasites

We can control parasites by:

- Killing the worms within the body

- Reducing the chances of the animal becoming infected on pastures

The worms can be killed inside the host by giving it a drug. The drugs are given by drenching, tablets or injection. Ask your veterinarian when and how often you should treat your animals.

In order to cut down the chance of animals becoming infected:

- If possible, move stock to new pasture every one to two weeks.

- Young animals should be separated from old animals and allowed to graze fresh pasture first.

- If cattle, sheep and goats are kept in the same area, let the cattle graze the pasture before the sheep, as some worms which would infect the sheep will not infect the cattle.

- If animals are kept in an enclosure, removing the dung and disposing of it will prevent the animals picking up more worms or others becoming infected.

- Do not allow animals to graze on marshy ground or on pasture where the grass is very short.

- When animals have been treated, turn them out onto fresh pasture.

Deworming of calves

Many buffalo calves die due to round worm infestation. Calves should be dewormed starting from 15 days of age at 15 days’ interval with piperazine. Dose should be according to body weight.

Ethnoveterinary treatment

- Leaves of nirgundi (Vitex negundo), khorpad (Aloe vera), Neem seeds, kirayat (Andrographis paniculata), akamadar (Calotrophis) are to be taken at 1 kg each.

- All are to be ground well by sprinkling little water and filtered and 4 liters of herbal mixture can be obtained. This has to be stored for 3 days.

- Then 30 ml of the extract is taken and administered for one adult sheep or goat.

- For younger sheep or goat less than 3 months old 10 ml has to be administered orally. For adult cattle 100 ml has to be administered.

- The dewormer arrest loose motion and result in solid dung and it is free from obnoxious odor. It increases grazing efficiency of animals and they look healthy.

Parasitic Gastroenteritis in Ruminants

Including: Cooperia onchophora, Ostertagia ostertagi, Teladorsagia circumcincta, Trichostrongylus spp., Haemonchus spp. (Barbers Pole Worm), Nematodirus battus

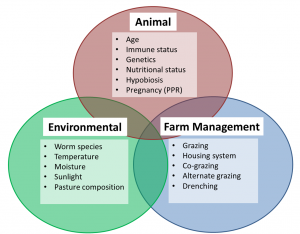

Factors that affect parasite infection in livestock

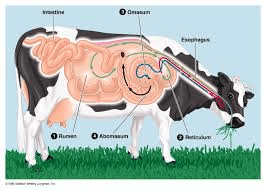

Gastrointestinal nematodes (GI nematodes or gut roundworms) are major contributors to reduced productivity in cattle, sheep and goats all over the world. Parasitic Gastroenteritis (PGE) is the condition caused by large numbers of gastrointestinal nematodes that reside in the gut (abomasum and intestines) of the ruminant host.

The clinical signs of PGE vary depending on nematode species and abundance. PGE is primarily a disease of lambs and first season grazing cattle. The most profound effect of parasitism in both sheep and cattle is the sub-clinical production losses (i.e., not visually obvious), the true extremity of which farmers are unlikely to be aware.

Understanding Parasite Biology

The main species of GI nematode that are of veterinary importance in temperate climates are:

- Cooperia onchophora (Cattle)

- Ostertagia ostertagi (Cattle)

- Teladorsagia circumcincta (Sheep)

- Trichostrongylus spp. (Sheep and cattle)

- Haemonchus spp.(Mainly sheep but sometimes cattle)

- Nematodirus battus (Mainly sheep but sometimes cattle)

Some species of gut parasite have their own disease page on Farm Health Online as their epidemiology and clinical signs do vary. However, nematode infections are almost always a mixture of species so this page provides a broad overview of GI nematodes in cattle and sheep.

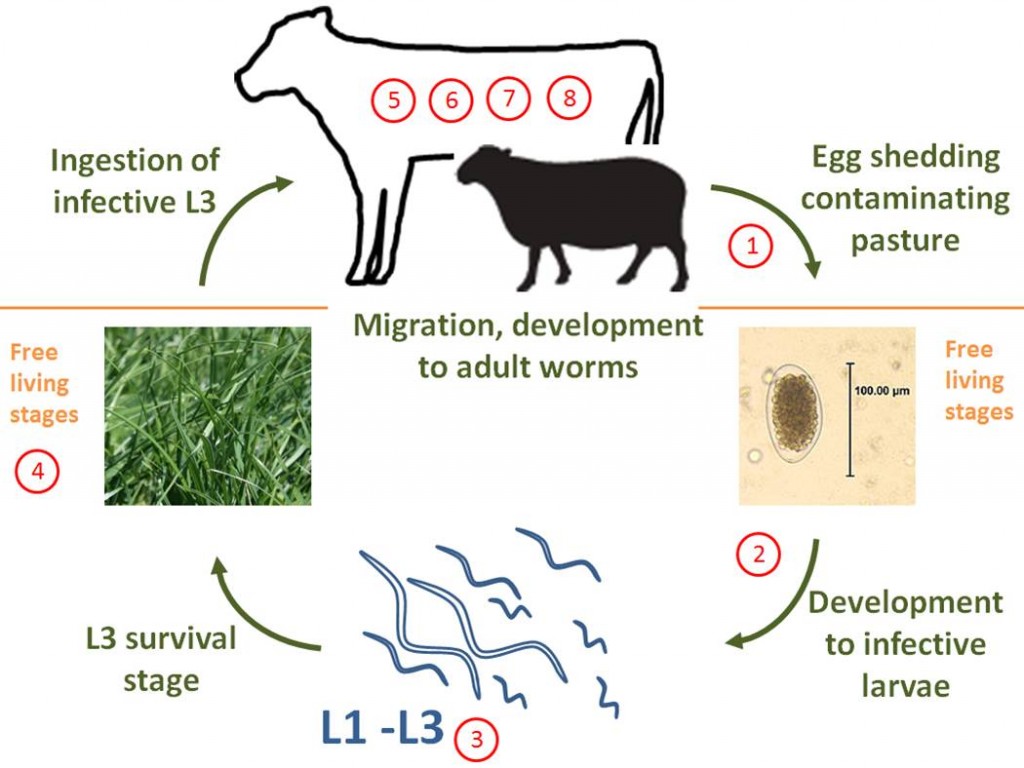

The Life Cycle of GI Nematodes

Most GI nematodes have a simple direct lifecycle, although there are species-specific variability in development rates and predilection site. The lifecycle has two distinct phases; 1) within the host, and 2) the free-living stage where the parasite is developing in the environment. The basic parasitic gut worm lifecycle follows the steps below:

- Unembryonated eggs are passed from the host in feces*

- The eggs embryonate and develop into first stage larva (L1)

- The L1 undergo two more molts (L2 and L3), and hatch out of the egg shell and migrate out of the fecal pat onto the pasture as L3

- The L3 are infective at this stage and need to survive on the pasture until ingested by the ruminant host

- Once consumed the L3 migrate to the gut** and borrow into the gut lining

- Here they undergo two more molts (as L4 and L5) before emerging*** and maturing into adult worms

- The male and female worms reproduce

- The female worms lay eggs which are passed out in the feces

*Fecal samples can be collected and the number of eggs can be counted – this is called a Fecal Egg Count. These can be used to monitor worm burden and make treatment decisions. However FECs do have their limitations especially in cattle.

**Exact predilection site depends on worm species (e.g., abomasum or small intestine)

***This is where the pathogenesis occurs

GI nematode lifecycle

Cattle, sheep and goats can be infected by three types of helminth, or internal parasite. These are roundworm, tapeworm and fluke. This paper discusses the control of roundworm in these three species. Roundworms are found all year round and live in many sites in the animal, including the eye, lungs, the body cavity, beneath the skin and most commonly, the gastro-intestinal tract.

They lay large numbers of eggs, which are usually passed out in the dung of the host animal. In some cases the eggs hatch in the intestine and the larvae are passed out. There are 14 different roundworms affecting sheep, goats and cattle in this country.

It is important to understand the life-cycle of the roundworms so as to implement a strategic and effective dosing program. Very simply, roundworms live, usually in the intestine of the animal, where they suck blood, eat tissue or eat the stomach contents thus depriving the animal of nutrients.

The female will lay eggs which pass out with the dung. If conditions are right the larvae hatches in a few days, then goes through a series of processes until it reaches a stage where it can infect the animal. In some helminthes, this process involves an intermediary host.

The animal becomes infected while grazing, eating food or water contaminated with the larvae or eating the intermediate host, such as a mite. The larvae mature in the intestine and mate. The female lays her eggs in 2 – 4 weeks after infection and begins the cycle again.

Life-cycle of the roundworm (single host)

Roundworms of Cattle, Sheep and Goats of Southern Africa

Eye worm (Thelazia) In cattle, rarely in sheep. Not particularly harmful and does not cause ophthalmia, however a large number may make the animal more susceptible to ophthalmia.

Abdominal worm (Setaria cervi) Found in the abdomen of cattle, sheep and horses. Quite harmless, the larvae reach the bloodstream and are transmitted by blood sucking flies.

Lungworms Found in cattle, sheep and goats, horses, mules and donkeys. Can be very harmful, especially in sheep and goats. The worms live in the small bronchi of the lungs. When eggs are laid, they are coughed up and swallowed by the animal. The sheep can get respiratory complications, lose condition rapidly and die.

Zig-zag worm (Gongylonema) Found in the membrane lining the gullet and the rumen, these appear to be completely harmless, even in large numbers.

Parafilaria Bovicola (Parafilariasis) Only affecting cattle, it lives in the subcutaneous tissue on the forequarters. It causes a large subcutaneous lesion of green/yellow or dark red appearance; looking like bruising (false bruising). The lesion is the reaction of the animal’s body to the irritation caused by the parasite.

Although the health of the cattle does not seem to be harmed by the parasite, at slaughter, large parts of the carcass are discarded due to the lesions and the carcass is down-graded. As flies are an intermediate host to this parasite, it is important to control biting flies. (See Fly Control)

Wireworm (Haemonchus contortus) Occurring in sheep, goats and cattle, this worm is the most common and most harmful of the roundworms. They suck blood, spilling so much that the contents of the abomasums, where they live, turn red.

Anaemia develops, the animals get an oedematous swelling under the jaw and become thin, weak and breath rapidly. The larvae require moisture for their development and therefore there are often massive infestations after the rains begin. However, they can survive in the undeveloped stage through the winter if there is some moisture around.

Brown Stomach-worm (Ostertagia) lives in the abomasums of cattle, sheep and goats, and is particularly troublesome in Angora goats. The life-cycle is similar to that of the wireworm and symptoms of infestation are similar.

Bankrupt worm (Trichostrongyles and Cooperia) infect cattle, sheep and goats, living in the small intestine and abomasums. Sheep are most affected and can die from heavy infestations. The life-cycle is similar to that of the wireworm except that the bankrupt worm can survive through a dry winter. The larvae can survive in the egg for a year if conditions are not favourable for hatching.

The eggs will hatch with the first rains and when animals graze these pastures a massive infection will result. The sheep start purging, become paralysed in the hindquarter and some die. Strongyloides does not even need to be swallowed but can burrow into the skin of the legs, then migrates to the lungs, causing respiratory distress and diarrhoea.

The cattle bankrupt worm Cooperia is fairly common and is quite harmful, but not as devastating as in sheep.

Hookworms This is a large family of blood-sucking worms which live in the small intestine of their hosts, which include cattle, sheep, goats, horses, dogs, cats and man. They suck large amounts of blood from the host and cause bleeding into the intestine. Young animals are particularly affected.

The hookworm enters the body of the animal or man through the skin, migrates via the bloodstream to the lungs, is coughed up and swallowed to the intestine, where it begins the cycle again. A sheep hookworm Gaigeria causes the host sheep to lose some much blood that 24 can kill a healthy adult sheep in a few days.

Ascaris worm (Ascaris vitulorum) Found only in calves kept in pens, it is closely related to the Ascaris of pigs. The worms lay many eggs which pass into the pen via the dung and can infect a contaminated area for years. Pens must be regularly cleaned and disinfected.

Nodular worm (Oesophagostomum) Commonly infecting sheep and goats, while different species infect cattle, pigs and man. The worms form protective nodules in the intestine of the host, making them very difficult to kill. Toxic secretions from the worm cause erosion of the gut wall and eventually these secretions enter the body of the animal, basically poisoning the whole system. Sheep grow thin and weak, emaciated and die.

Large-mouthed worm (Chabertia ovina) Lives in the large intestine of cattle, sheep and goats. Its habits and life cycle are similar to the hookworms. They cause anaemia and loss of condition.

Whipworm (Trichuris) A relatively harmless worm which lives in the mucous membranes of the large intestine of cattle, sheep and goats. It is sometimes mistaken for the nodular worm, but causes far less damage.

Worm Nodules of Cattle (Onchocerca) The worms live in subcutaneous nodules, especially along the brisket. The larvae enter the bloodstream and are swallowed by blood-sucking midges, which then transmit the infection to other animals. Although the worm is not harmful to the animal, the infected carcass is down-graded and revenue from beef is lost.

Read Also: Worm infection among Poultry Birds: Types, Causes, Prevention Control and Treatment

SYMPTOMS OF ROUNDWORM INFESTATION

Some animals can carry a worm burden and appear unaffected, showing no symptoms. Young animals and animals under stress due to malnutrition, disease etc are more affected. However, even healthy adults, if they have a large worm burden will show symptoms and a loss of production.

Young animals show stunted growth and development, are pot-bellied , have poor coats and may have diarrhoea. Animals with many blood-sucking worms can shows signs of anaemia. In extreme cases they may die.

PREVENTION AND CONTROL

• Animals in good condition are definitely more able to tolerate worm infestations – another good reason for feeding livestock well. Young animals are more susceptible and require more care.

• Calf pens, dairy yards, collecting pens, kraals, anywhere that animals are in constant close confinement should be regularly cleaned and disinfected and manure collected and disposed of to kill infective eggs and larvae.

• Pasture rotation and paddock resting will help to break the cycle. Where paddocks are heavily dunged, discing or harrowing the manure into the ground can help.

• Avoid grazing animals in low-lying wet areas in summer if possible.

• Identify the species of worms on your farm by taking dung samples into the laboratory for egg counts and identification. The worming regime will depend on these results. It is also a good idea to take samples before and after dosing to check the effectiveness of the product against the worms on your property.

A sample dosing programme, depending on the worm load and species present is to dose all animals 3 weeks after the first heavy rain to kill infective larvae picked up with the rainfall.

Dose again in the middle of summer and after the first frosts in Autumn, so that animals go into the Winter clean. Young stock, particularly dairy calves will requie more frequent dosing.

• Anthelmintics (dosing medicines) come in various forms – injectables, by mouth and pourons. Some have combination effects against roundworm and fluke.

DECTOMAX INJECTABLE is effective against most roundworms of sheep, cattle and goats, parafilaria and sheep scab.

FINIWORM is registered for cattle, sheep, goats, horses and pigs and is effective against most roundworm including migrating lungworm, nodular worm.

NILZAN BOLUS is an anthelmentic for the treatment and control of gastrointestinal and pulmonary nematode infestations and chronic fascioliasis in cattle.

SYSTAMEX is an effective treatment for susceptible strains of Small Brown Stomach Worm, (including inhibited larvae), Stomach Hair Worm, Barber’s Pole Worm, Small intestinal Worm, Thin-necked Intestinal Worm, Nodule Worm, Black Scour Worm, Hookworm, Tapeworm and Lungworm in cattle.

VALBAZEN® is remedy for roundworms and milk tapeworms in cattle. Prevents roundworms eggs present in the animal at dosing from hatching.

VALBAZEN® FOR SHEEP AND GOATS is a remedy for roundworm, lungworm, milk tapeworm and liver fluke in sheep and goats. Prevents roundworm eggs present in the animal at dosing from hatching.

Types of Worms and their Methods of Control

Following worms are described below: Liver flukes, Tape worms, Lung worms, Roundworms.

1) Liver Flukes

Local names:

Embu: nthambara / Gikuyu: thambara cia mani / Kamba: ntambaa / Kipsigis: sungurutek / Luo: ochwe / Maragoli: ovoveyi / Meru: nthanthara / Samburu: ikurui, lemonyua / Somali Ethiopia: faraqle / Somali Kenya: sogul / Masai: Osinkirri

Family: Trematoda

Description: Parasite

Introduction

There are two important species of liver flukes in Kenya: fasciola gigantica and fasciola hepatica. The former is more important, being found throughout the lower warmer parts of the country. As the name suggests it is very large, more than twice the size of fasciola hepatica, which is found in the cooler highland areas of the country, and also in the temperate zones of the world such as Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand.

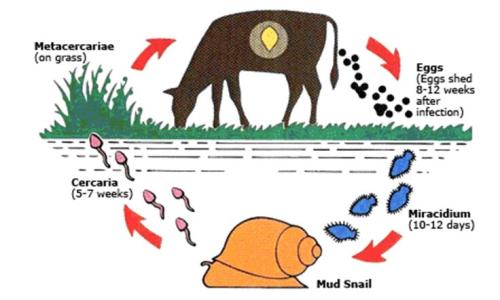

The life cycle of liver flukes involves a snail, which acts as an intermediate host. If there is no snail there will be no flukes. The snail involved requires still, stagnant water to survive; swift running water does not suit it. Swamps, ponds, lakes with a marshy edge and pools of water edged by vegetation are danger zones for grazing animals.

Cattle, sheep and goats are mainly affected, although other animals such as donkeys, horses, and many species of wildlife such as buffalo can also be infested. Humans can also be infested with liver flukes.

As the name suggests, the liver fluke attacks the liver.

Three forms of illness can occur:

- Flukes can cause sudden death, from liver failure and from internal bleeding, when large numbers of immature flukes migrate through and cause damage to liver tissue. This clinical picture is common in young sheep.

- Flukes can also cause a chronic wasting disease accompanied by anaemia and oedema (swelling). The oedema is typically located on the lower jaws (“bottle jaw”) and on the lower part of the belly. This is the most common picture in cattle.

- Liver lesions due to flukes are the causative factor in Infectious Necrotic Hepatitis (Black Disease), predominantly a disease of sheep aged between 2 – 4 years, but aso occurs in young cattle. Specific bacteria (Clostridia) multiply in liver lesions caused by migrating flukes and release toxins. Sudden death is the result.

Adult of Fasciola hepatica

(c) Wikipedia

Life cycle of liver flukes

Knowledge of the life cycle of the liver fluke is an aid in understanding how to control the disease.

The intermediate host snails for Fasciola gigantica and Fasciola hepatica may differ but in other respects the life cycle is the same.

- The life cycle begins with the eggs of the fluke which mature in the bile ducts in the liver, pass down the ducts, into the gut and are excreted with the faeces.

- Once outside in the environment, which must contain water, the eggs hatch, releasing an active stage, called miracidia. Temperature and time are critical in the early stages for the development of the miracidia- above 5-6 C, and best between 25-24C. Miracidia must find a suitable snail within 24-30 hours or they will die.

- The miracidia either actively invade a host snail or are eaten by a host snail.

- They then hatch in the snail’s gut and the next stage develops in the tissues of the snail.

- 5 to 8 weeks later another stage emerges from the snail and form resistant cysts attached to herbage or grass, where they are eaten by the final host – cattle, sheep, goat or other herbivores.

- Once ingested by the sheep or cow the immature fluke invade the gut wall, travel to the liver where they cause extensive damage to the liver tissue until they reach the bile ducts. Here they mature into adult flukes and start to lay eggs and the life cycle begins again. It takes 10-12 weeks from infestation until eggs start to be laid and shed with the faeces.

Mature flukes are long lived and sheep and cattle may be carriers for years.

Lifecycle of Fasciola hepatica

(c) Grace Mulcahy

Life cycle of a liver fluke

(c) uk.merial.com

Read Also: Importance of Feeding and Drinking Troughs for Ruminant Animals

Signs of Liver Fluke disease

The severity of clinical signs depends on the number of parasites ingested by the host animal over a short period of time. Cattle appear to be able to develop an immune reaction to fluke infestation, but sheep do not.

The acute form of the disease is more common in sheep than in cattle.

- It occurs 5 to 6 weeks after the ingestion of large numbers of metacercariae. There is a sudden invasion of the liver by masses of young liver flukes.

- Sudden death, especially in sheep, can occur due to internal bleeding and liver failure and also due to sudden release of toxin by bacteria (Clostridia) multiplying rapidly in the liver lesions (Black Disease)

- The

Frequently Asked Questions

We will update this section soon.