As a beginner, there are most times many questions you may wish to ask concerning your ruminant animals and am sure that a question like this one: how do I know when my ruminants are suffering from worm infestation must be one of them.

Secondly, you may also wish to know the signs and symptoms and how to go about their treatment. Don’t worry as we are going to discuss all that below:

There are many signs that can indicate worm infestation in ruminant animals and these include: Loss of weight due to the competition between the animals and the worms for digested feeds, the animals begin to lose weight, the animals may lose appetite, there could be diarrhea and worms may be seen on their feaces.

There are times when worm infestation may cause the animals to cough. Any or all of these signs may make worm infestation a suspect among your ruminant animals. However, these signs are not confirmatory of the condition, further steps must still be taken to confirm.

Now let us go to how often your ruminant animals should be treated against worm infestation and which drug is best for you to use: As a routine, it is good that you deworm your animals at least once in three months or as recommended by your consultant depending on the location of your farm.

Apart from routine deworming, it may be recommended any time signs of worm infestation are seen on the animals. As for the ideal drugs, there are countless number of dewormers that can be used with good results. Some of them are liquid, some bolus while others are in powdery form. The choice of the drugs should depend on your consultant’s recommendation.

Livestock Animals Parasites

Parasites are a major cause of disease and production loss in livestock, frequently causing significant economic loss and impacting on animal welfare. In addition to the impact on animal health and production, control measures are costly and often time-consuming. A major concern is the development of resistance by worms, lice and blowflies to many of the chemicals used to control them.

Planned preventative programs are necessary to minimise the risks of parasitic disease outbreaks and sub-clinical (invisible) losses of animal production, and to ensure the most efficient use of control chemicals.

Integrated parasite management programs aim to provide optimal parasite control for the minimal use of chemicals by integrating pre-emptive treatments, parasite monitoring schedules and non-chemical strategies such as nutrition, genetics and pasture management.

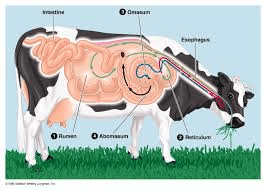

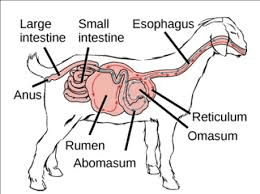

Internal parasites of ruminants

Parasites

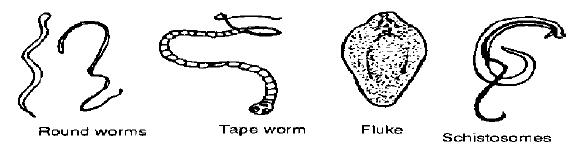

A parasite lives in or on another animal and feeds on it. All animals and humans can become infected with parasites. Ruminants can be infected with several types of worms.

Types of parasites

- Roundworms are small, often white in color, and look like threads. Different roundworms are found in all parts of the gut and the lungs.

- Tapeworms are long, and flat and look like white ribbons. They consist of many segments and live in the intestine.

- Flukes are flat and leaf-like, they live in the liver. Schistosomes are small and worm-like, both infect animals kept on wet, marshy ground as their eggs develop in water.

- The roundworms, flukes and schistosomes lay eggs which pass out of the animal in the dung onto the pasture.

- Tapeworms produce eggs in the segments which break off and pass out in the dung. Animals become infected when they graze the pasture.

The effect of parasites on the animals

- Parasites feed on the food in the gut and on the blood of the host.

- The animal becomes weak and loses weight or does not gain weight. It can develop diarrhea, which in sheep makes the wool wet and attracts flies.

- Eventually the host becomes so weak that it dies. Young animals are especially affected by parasites.

Animals becoming infected with parasites

Read Also: How to treat Ruminant Animal Diseases

Control of parasites

We can control parasites by:

- Killing the worms within the body

- Reducing the chances of the animal becoming infected on pastures

The worms can be killed inside the host by giving it a drug. The drugs are given by drenching, tablets or injection. Ask your veterinarian when and how often you should treat your animals.

In order to cut down the chance of animals becoming infected:

- If possible, move stock to new pasture every one to two weeks.

- Young animals should be separated from old animals and allowed to graze fresh pasture first.

- If cattle, sheep and goats are kept in the same area, let the cattle graze the pasture before the sheep, as some worms which would infect the sheep will not infect the cattle.

- If animals are kept in an enclosure, removing the dung and disposing of it will prevent the animals picking up more worms or others becoming infected.

- Do not allow animals to graze on marshy ground or on pasture where the grass is very short.

- When animals have been treated, turn them out onto fresh pasture.

Deworming of calves

Many buffalo calves die due to round worm infestation. Calves should be dewormed starting from 15 days of age at 15 days’ interval with piperazine. Dose should be according to body weight.

Ethnoveterinary treatment

- Leaves of nirgundi (Vitex negundo), khorpad (Aloe vera), Neem seeds, kirayat (Andrographis paniculata), akamadar (Calotrophis) are to be taken at 1 kg each.

- All are to be ground well by sprinkling little water and filtered and 4 liters of herbal mixture can be obtained. This has to be stored for 3 days.

- Then 30 ml of the extract is taken and administered for one adult sheep or goat.

- For younger sheep or goat less than 3 months old 10 ml has to be administered orally. For adult cattle 100 ml has to be administered.

- The dewormer arrest loose motion and result in solid dung and it is free from obnoxious odor. It increases grazing efficiency of animals and they look healthy.

Parasitic Gastroenteritis in Ruminants

Including: Cooperia onchophora, Ostertagia ostertagi, Teladorsagia circumcincta, Trichostrongylus spp., Haemonchus spp. (Barbers Pole Worm), Nematodirus battus

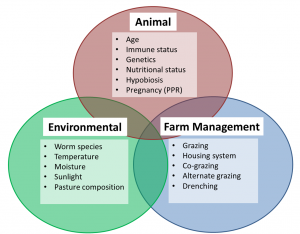

Factors that affect parasite infection in livestock

Gastrointestinal nematodes (GI nematodes or gut roundworms) are major contributors to reduced productivity in cattle, sheep and goats all over the world. Parasitic Gastroenteritis (PGE) is the condition caused by large numbers of gastrointestinal nematodes that reside in the gut (abomasum and intestines) of the ruminant host.

The clinical signs of PGE vary depending on nematode species and abundance. PGE is primarily a disease of lambs and first season grazing cattle. The most profound effect of parasitism in both sheep and cattle is the sub-clinical production losses (i.e., not visually obvious), the true extremity of which farmers are unlikely to be aware.

Understanding Parasite Biology

The main species of GI nematode that are of veterinary importance in temperate climates are:

- Cooperia onchophora (Cattle)

- Ostertagia ostertagi (Cattle)

- Teladorsagia circumcincta (Sheep)

- Trichostrongylus spp. (Sheep and cattle)

- Haemonchus spp.(Mainly sheep but sometimes cattle)

- Nematodirus battus (Mainly sheep but sometimes cattle)

Some species of gut parasite have their own disease page on Farm Health Online as their epidemiology and clinical signs do vary. However, nematode infections are almost always a mixture of species so this page provides a broad overview of GI nematodes in cattle and sheep.

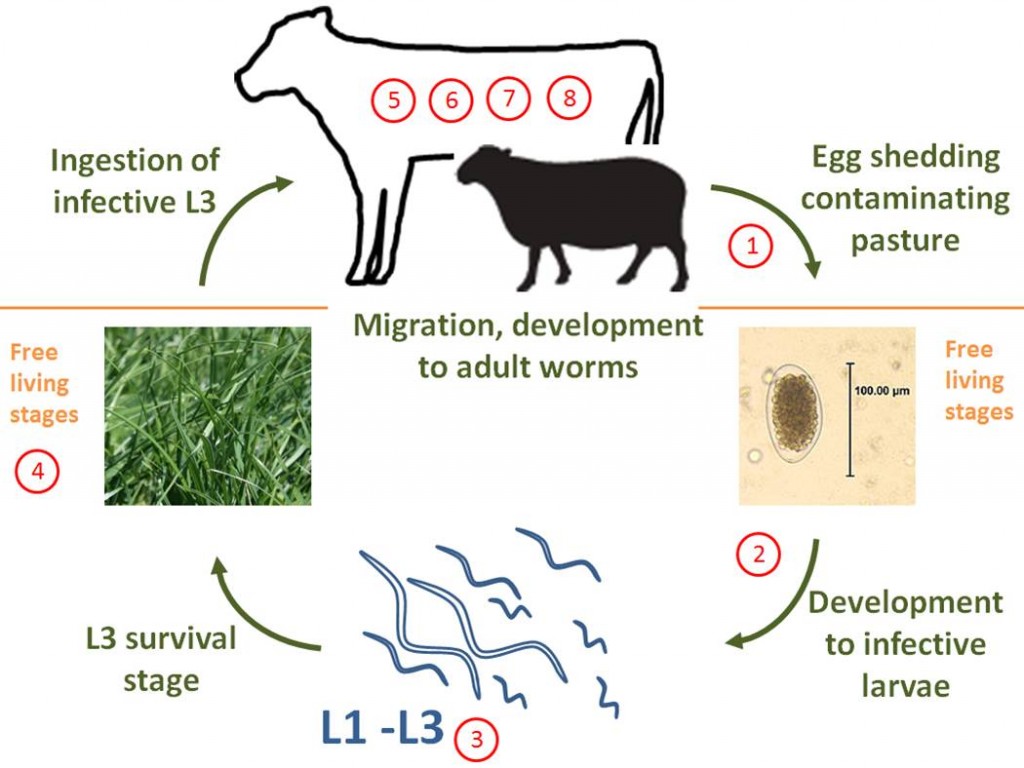

The Life Cycle of GI Nematodes

Most GI nematodes have a simple direct lifecycle, although there are species-specific variability in development rates and predilection site. The lifecycle has two distinct phases; 1) within the host, and 2) the free-living stage where the parasite is developing in the environment. The basic parasitic gut worm lifecycle follows the steps below:

- Unembryonated eggs are passed from the host in feces*

- The eggs embryonate and develop into first stage larva (L1)

- The L1 undergo two more molts (L2 and L3), and hatch out of the egg shell and migrate out of the fecal pat onto the pasture as L3

- The L3 are infective at this stage and need to survive on the pasture until ingested by the ruminant host

- Once consumed the L3 migrate to the gut** and borrow into the gut lining

- Here they undergo two more molts (as L4 and L5) before emerging*** and maturing into adult worms

- The male and female worms reproduce

- The female worms lay eggs which are passed out in the feces

*Fecal samples can be collected and the number of eggs can be counted – this is called a Fecal Egg Count. These can be used to monitor worm burden and make treatment decisions. However FECs do have their limitations especially in cattle.

**Exact predilection site depends on worm species (e.g., abomasum or small intestine)

***This is where the pathogenesis occurs

GI nematode lifecycle

Roundworms of Cattle, Sheep and Goats of Southern Africa

Read Also: Worm infection among Poultry Birds: Types, Causes, Prevention Control and Treatment

SYMPTOMS OF ROUNDWORM INFESTATION

PREVENTION AND CONTROL

Types of Worms and their Methods of Control

Following worms are described below: Liver flukes, Tape worms, Lung worms, Roundworms.

1) Liver Flukes

Embu: nthambara / Gikuyu: thambara cia mani / Kamba: ntambaa / Kipsigis: sungurutek / Luo: ochwe / Maragoli: ovoveyi / Meru: nthanthara / Samburu: ikurui, lemonyua / Somali Ethiopia: faraqle / Somali Kenya: sogul / Masai: Osinkirri

Introduction

- Flukes can cause sudden death, from liver failure and from internal bleeding, when large numbers of immature flukes migrate through and cause damage to liver tissue. This clinical picture is common in young sheep.

- Flukes can also cause a chronic wasting disease accompanied by anaemia and oedema (swelling). The oedema is typically located on the lower jaws (“bottle jaw”) and on the lower part of the belly. This is the most common picture in cattle.

- Liver lesions due to flukes are the causative factor in Infectious Necrotic Hepatitis (Black Disease), predominantly a disease of sheep aged between 2 – 4 years, but aso occurs in young cattle. Specific bacteria (Clostridia) multiply in liver lesions caused by migrating flukes and release toxins. Sudden death is the result.

| Adult of Fasciola hepatica |

|

(c) Wikipedia |

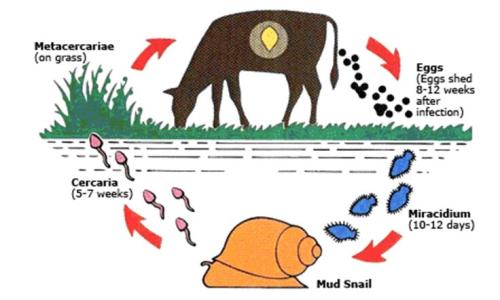

Life cycle of liver flukes

- The life cycle begins with the eggs of the fluke which mature in the bile ducts in the liver, pass down the ducts, into the gut and are excreted with the faeces.

- Once outside in the environment, which must contain water, the eggs hatch, releasing an active stage, called miracidia. Temperature and time are critical in the early stages for the development of the miracidia- above 5-6 C, and best between 25-24C. Miracidia must find a suitable snail within 24-30 hours or they will die.

- The miracidia either actively invade a host snail or are eaten by a host snail.

- They then hatch in the snail’s gut and the next stage develops in the tissues of the snail.

- 5 to 8 weeks later another stage emerges from the snail and form resistant cysts attached to herbage or grass, where they are eaten by the final host – cattle, sheep, goat or other herbivores.

- Once ingested by the sheep or cow the immature fluke invade the gut wall, travel to the liver where they cause extensive damage to the liver tissue until they reach the bile ducts. Here they mature into adult flukes and start to lay eggs and the life cycle begins again. It takes 10-12 weeks from infestation until eggs start to be laid and shed with the faeces.

Mature flukes are long lived and sheep and cattle may be carriers for years.

|

Lifecycle of Fasciola hepatica |

|

(c) Grace Mulcahy |

| Life cycle of a liver fluke |

|

(c) uk.merial.com |

Read Also: Importance of Feeding and Drinking Troughs for Ruminant Animals

Signs of Liver Fluke disease

The acute form of the disease is more common in sheep than in cattle.

- It occurs 5 to 6 weeks after the ingestion of large numbers of metacercariae. There is a sudden invasion of the liver by masses of young liver flukes.

- Sudden death, especially in sheep, can occur due to internal bleeding and liver failure and also due to sudden release of toxin by bacteria (Clostridia) multiplying rapidly in the liver lesions (Black Disease)

- The

- Triclabendazole and Fenbendazole should be given at the rate of 10mg and 8mg respectively per kg body weight by mouth.

- Trodax or nitroxynil given at 34 % solution for cattle administered subcutenously at 1.5ml per 50kg body weight and may be repeated as may be necessary.

- Oxyclozanide or Flukanide or Ranide are available from different pharmaceutical manufacturers and should be used according to the manufacturer’s recommendation.

2) Tape worms (Flat worms)

Introduction

Adult tapeworms in the intestine have little effect on the health of adult farm animals. Large numbers of tapeworms in the intestines of young animals may cause stunting and occasionally trigger severe colic.

The general life cycle of tapeworms occurs in two hosts, the final host (e.g. dog) and the intermediate host (e.g. cow).

Life cycle of tapeworms that live in the intestines of cattle, sheep and goats

The eggs of mature tapeworms that live inside the intestine of a cow, sheep or goat (final host) can only develop into another adult tapeworm after going through an intermediate stage inside the organs of an intermediate host.

The intermediate hosts of the common tapeworms of ruminants are small mites that live on the pasture and are ingested by the final host during grazing.

1. Monieza benedeni

Monieza is found in the intestine of cattle, sheep, goats and occurs in most parts of the world. The life cycle includes the final host (ruminant) and the intermediate host – small mites living in large numbers on the pasture.

These mites are eaten by grazing animals and develop in the intestine into adult tapeworms. The adult tapeworm is 1-6 meters long, 16mm wide and lives for only about 3 months in the final host. When the tapeworm dies it is shed with the faeces.

|

|

|

| Monieza tapeworm segments in calf dung- segments are wider than long | Monieza in lamb intestine | Knot of worms from intestine-segments are wider than long |

| (c) Sheelagh S. Lloyd |

(c) Sheelagh S. Lloyd |

(c) Sheelagh S. Lloyd |

2. Avittelina species

3. Thysaniezia giardi

Clinical signs of adult tapeworm infection

Tapeworms in the intestine of adult cattle, sheep or goats do not cause any serious disease. Very large numbers of tapeworms in the intestine of calves and lambs can lead to stunting, pot belly, diarrhoea and constipation and also colic due to obstruction of the intestinal passage.

Diagnosis

This is made by observing tapeworm segments in the faeces or intestines, or in the laboratory by checking under the microscope for the presence of tapeworm eggs in the faeces.

At slaughter

- Tapeworms may be present in the intestine or in the bile ducts.

- The carcass may be pale and thin

- The walls of the intestines may show ulcerations and inflammation caused by hooks of tapeworms

- Tapeworm segments or a whole adult tapeworm can be seen in the faeces.

Prevention and Treatment

There are no preventive measures against tapeworms living in the intestine of ruminants.

Treatment

As the tapeworm has a limited lifespan and is excreted with the faeces it is not necessary to treat adult cattle, sheep and goats against tapeworms. Treatment may become necessary in heavily infected young calves, lambs and kids. Some broad spectrum anthelmintics are also active against tapeworms (see below).

- Use of anthelminthic drugs that also act on tapeworms is the only effective treatment method (read label and instructions carefully, some anthelminthic drugs have no effect on tapeworms!).

- Niclosamide, Praziquantel, Albendazole, Fenbendazole, and Oxfenbendazole are effective against tapeworms in cattle, sheep and goats.

|

Tapeworm segments |

Taenid eggs migrating away from the faeces (white arrows) leaving a trail of eggs on the ground (black arrows) |

|

(c) S. Lloyd |

(c) S. Lloyd |

| Tapeworm cyst in muscle A: head, B: bladder | Tapeworm segment (longer than wide) |

|

(c) S. Lloyd |

(c) S. Lloyd |

Tapeworms in intestines of dogs causing cysts in cattle, sheep and goats

- Tapeworms living in the intestine of dogs are of great significance as they cause cysts and dangerous chronic disease in ruminants and also in humans.

- Life cycle of tapeworms that live in the intestines of dogs and cause disease in cattle, sheep, goats and humans (!)

Dogs harbour specific tapeworms in their intestines and excrete the eggs into the environment, including onto pastures. Cattle, sheep, goats (and humans) are the intermediate hosts.

If cattle, sheep and goats swallow tapeworm eggs excreted by dogs, the intermediate stages of these tapeworms develop into cysts inside the body of the cow, sheep, goat (or human).

Depending on location of the cysts inside the body (often found in liver, lung, also in the brain) this has very serious effects on the health, leading to chronic and ultimately deadly disease.

The adult tapeworm lives in the intestine of the dog (final host) and produce eggs, which are excreted inside the tapeworm segments (called proglotid). After the segments have been shed with the faeces they disintegrate and release invisible eggs into the environment.

These eggs can survive for a long time on the pasture. The invisible eggs are then eaten by the cow, sheep, goat (intermediate host) during grazing and transform into a cyst.

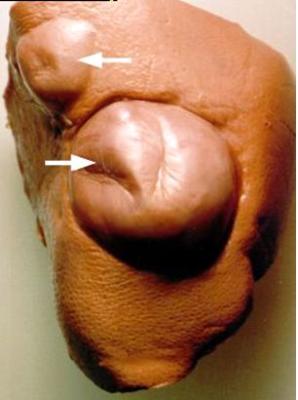

The most dangerous tapeworm found in dogs is Echinococcus. The adults of this small species of tapeworm live in the intestine of the dog (final host), causing almost no harm to the dog.

Eggs are shed in dog faeces, then ingested by intermediate hosts (cattle, sheep, goats, humans) and develop into cysts in the organs of the intermediate host (esp. liver, lung, also brain).

These so called hydatid cysts continue to grow and also form multiple daughter cysts, causing severe damage to the organs of the intermediate host.

Read Also: How to Identify the Particular Disease Affecting your Ruminant Animals

When organs of the intermediate host containing cysts are ingested by dogs (e.g. at slaughter) the cysts will again develop into an adult tapeworm living inside the intestine of the final host (dog) and the cycle starts again.

|

In sheep, goats, cattle and also pigs Taenia Hydatigena larva (long necked bladder worm)causes large cyst of 5-8 cm in diameter, containing a clear watery fluid often attached to the liver. (c) Dr. John W. McGarry and the School of Vet Science in Liverpool |

1) Taenia hydatigena

This is a dog tapeworm and cattle, sheep, goats and also pigs are intermediate hosts. If dogs have access to the liver or peritoneal tissues of infected cattle they become infested with the adult tapeworm.

2) Larval tape worm infestation in cattle

This is a very small and short dog tapeworm.It is the most dangerous tapeworm of dogs because it forms many hydatid cysts that continue to grow in the organs of the intermediate hosts: sheep, goat, cattle and also humans. These cysts are mostly located in the liver and lungs, sometimes also in the brain. They can slowly grow to a very large size. People living in very close association with infected dogs are especially at risk.

|

| Echinococcus hydatid liver cyst. Fluid filled large opaque cyst, the most common diameter being 5.0 – 10.0 cm. When mature, cysts may reach 0.5 meter in diameter depending on available space |

|

(c) Dr. John W. McGarry and the School of Vet Science in Liverpool |

Symptoms of Tapeworm cysts in the intermediate hosts

Tapeworms have no apparent effect in the dog (main host).

In intermediate hosts (sheep, goat, cattle, human) symptoms vary depending on the organ of the body which is affected. Coenurus cerebralis, can reach the brain of intermediate hosts and cause staggering, blindness, head deviation, stumbling and paralysis.

This condition is known in livestock as gid or sturdy. Palpation of the skull may reveal a soft spot and in very few cases it may be possible for a skilled veterinary surgeon to remove the cyst.

Echinococcus cysts cause symptoms that depend very much on the location of the cysts; symptoms can be central nervous (circling disease in sheep) or chronic, when cysts are located in the liver or lung.

Diagnosis

Lesions in livestock are normally found during meat inspection.

Prevention and control of Tapeworms in dogs

Dogs must never be fed raw slaughterhouse offal (lung, liver) or raw brain tissue from ruminants.

Dogs must be dewormed regularly (4xper year) with an anthelmintic drug that is effective against tapeworms (read label and instructions carefully, some anthelmintic drugs have no effect on tapeworms!).

After slaughter it is important to dispose of and/or destroy all condemned organs and tissues that contain cysts in such a way, that dogs and other scavengers (Hyena) cannot gain access.

Ensure the following:

- Regular deworming of dogs against tapeworms

- Good meat inspection procedures by qualified meat inspectors and destruction or correct and safe disposal of infected tissues and meat (dispose offals into deep concrete pit that can be closed properly)

- Fencing of slaughter houses with dog proof fences will keep stray dogs away and prevent them from eating condemned meat that may be infected with cysts.

- When living in association with dogs, observe strict personal hygiene: always wash your hands thoroughly with soap after having contact with the dog. Always wash your hands thoroughly with soap before preparing food or eating. Children playing with dogs are at a particularly high risk of infection! Infected dogs licking children’s hands or faces can transmit the tapeworm eggs to them! Dogs living close to children must be dewormed very regularly.

Read Also: The Principles and Methods of Soil and Water Conservation

Treatment of tapeworm cysts

Treatment of tapeworm cysts is not possible in livestock.

Treatment of hydatid cysts in humans is difficult and sometimes requires surgical removal of thr cysts. Treatment is not always successful – in such cases the disease is fatal – the patient dies!

Tapeworms in the intestines of humans

Taenia saginata

This is a tapeworm of humans, it causes abdominal discomfort. It is a very long tapeworm, growing up to 15 metres long. Cattle are the main intermediate hosts. In cattle the cysts are located in skeletal and heart muscle tissue where they appear as small white oval nodules, visible to the naked eye.

These, if swallowed by a human, will again develop into a mature tapeworm. The tapeworm stage in cattle is also called measles. When measles are found at meat inspection the carcass can be detained and kept frozen below -10@C for minimum 10 days to destroy the cysts.

Alternatively infected meat can also be properly cooked to make it safe for human consumption. Carcasses with measles are either condemned or fetch a very low price.

Eating raw or undercooked meat that has not undergone meat inspection is highly dangerous and can result in infestation with Taenia saginata. Most measles are found in the heart, tongue, diaphragm and cheek muscles of cattle.

|

Adult Taenia saginata tapeworm, note scale. Humans become infected by eating raw or undercooked infected meat. In the human intestine the cysts (larval stage) develop over 2 months into adult tapeworms which can survive for years. They attach to and feed from the small intestine. |

|

(c) Center for Disease Control CDC Atlanta/Georgia |

Prevention

- Use of pit latrines to keep human waste away from pastures and grazing animals. The public should also be enlightened about the dangers of using human waste as fertilizer.

- Educating the public about the dangers of eating raw or partially cooked meat. The meat to be eaten by humans must be cooked properly or must be frozen below -10@C for minimum 10 days to kill the cysts.

- Infected humans must be identified through laboratory tests and treated against tapeworms.

Read Also: For how long can Ruminant Animals be starved? Find out

3) Round worms

Roundworms

(c) Dr. John W. McGarry and the School of Vet Science in Liverpool

Embu, Gikuyu, Meru: njoka / Gabbra: beni segara / Kamba: nzoka sya nda / Kipsigis: tiongik / Maragoli: tsinzoka / Samburu: ntumuai / Somali Ethiopia: goryan / Turkana: ngilomun /

Introduction

Roundworm infection, gastro-intestinal helminths or parasitic gastroenteritis, cause major economic loss in cattle, sheep and goat production.

The round worms are very small and vary in size from being visible to being almost invisible. – Several different species of worms with differing life cycles may be involved, but the symptoms they cause are all rather similar and difficult to differentiate in the living animal.

Most round worms feed on nutrients inside the host animal’s intestines. Certain worm species can attach to the lining of the stomach or guts, where they suck blood. These blood-sucking round worms cause more severe disease and anaemia and can kill young animals.

Immunity is acquired slowly and is generally incomplete. Good nutrition increases the resistance of livestock against round worms. Young animals are generally more at risk than adults.

But in sheep and goats the adults remain susceptible and suffer more from the effects of worms than in cattle. Especially ewes after lambing harbour large numbers of worms and can show diarrhoea and a drop in milk yield due to lowered immunity against the worms.

When treating animals with symptoms, the following should be considered:

- Provide adequate nutrition

- Treat all animals in a group as a preventive measure in order to reduce further pasture contamination

- Following treatment stock should NOT be moved to clean pasture as was previously recommended. The reason for this is that if any worms which are resistant to dewormers survive treatment then the clean pasture will become seeded with a completely resistant population of worms.

Resistance of worms against the drugs used (anthelmintic resistance) is a major and growing problem. Under-dosing, underestimation of body weight, overuse of anthelmintic drugs, random use of anthelmintics without a proper diagnosis, poor nutrition and rapid reinfestation all play a role in causing resistance.

In some countries, such as Australia and South Africa, anthelmintic resistance is such a serious problem that it threatens the economic viability of sheep farming. In order to prevent such a situation from developing anthelmintics must be used correctly and with restraint.

A good strategy is NOT to deworm the whole herd but to rather target specific animals or groups of animals, examples:

- Deworm young animals to prevent stunting

- Deworm ewes at lambing

- Selectively deworm those individual animals showing severe anaemia, visible as pale membranes around the eyes

Such a targeted deworming strategy will also reduce the amount of money spent on anthelmintics.

When suspecting resistance of worms against an anthelmintic drug the following test can be carried out:

- Immediately before deworming collect a pooled faecal sample from the group to be treated and send it to a laboratory for counting the number of worm eggs in the faeces (faecal egg count). This test is easy to perform in a lab and is not costly.

- 7-8 days after the treatment collect a second pooled faecal sample from the group and send it to the laboratory for a repeat faecal egg count.

- The comparison of worm egg numbers before and after the treatment will show whether the anthelmintic used is till effective or not.

Life cycle

The life cycle of the worms usually takes 2 to 3 weeks, but varies in relation to dry conditions, rainfall and temperature. The worm cycle is most active under cool and wet conditions leading to rapid build up of worm burdens in the stomachs and guts of grazing animals. It can almost stop when it is hot and dry.

Worm cycle:

- Eggs produced by the parasite are shed in the faeces of the animal onto the pasture.

- Out of these eggs hatch larvae which attach to grass and herbage.

- Larvae are then ingested by the grazing host.

Nematode parasites of cattle and sheep

1) Toxocara vitulorum

A round worm with a very specific life cycle, which does not affect mature cattle. It occurs in the intestines of suckling calves and is present in most tropical countries. The calves become infected before birth and also via the milk.

After ingestion the larvae penetrate the intestinal wall and migrate to other tissues of the host especially to the lungs, via the blood stream. The larvae are coughed up and then re-swallowed to re-enter the intestines, become adult worms in the intestines where they produce eggs. High numbers can lead to stunting of calves.

2) Haemonchus contortus

Also called the barber pole worm. It is a very aggressive and common blood-sucking stomach worm of cattle and sheep. It is found all over the world, but is less common or even absent from dry areas. It has a direct life cycle. Infective larvae can survive for several weeks on pasture under wet conditions.

After the larvae are ingested by the host, they become adults, attach to the lining of the stomach and start suckling blood. Depending on the numbers of worms present in the stomach this can lead to severe anaemia and even death in young animals.

Worms on the lining of the stomach are visible at post-mortem as very fine reddish small threads. They can easily be overlooked if the post mortem is not done carefully.

3) Trichostrongylus species

|

| Trichostrongylus tenuis are small hair like nematodes usually less than 7 mm long and difficult to see with the naked eye. |

|

(c) Dr. John W. McGarry and the School of Vet Science in Liverpool |

4) Cooperia species

Read Also: How Often to Clean a Ruminant Pen

5) Ostertagia species

6) Nematodirus species

7) Chabertia species

They are also known as the large mouthed bowel worms. They are found in the large intestine of most ruminants. The larvae penetrate and embed in the wall of the intestine.

The signs of round worm infection are shared by many diseases and conditions, but based on certain symptoms, grazing history, and season, a presumptive diagnosis can be made.

- Young animals are most often affected, but adults not previously exposed to infestation frequently show signs and succumb. Animals in a state of poor nutrition are more susceptible than animals in good condition.

- Ostertagia and Trichostrongylus infestations lead to profuse watery diarrhoea which is usually persistent.

- Haemonchus causes constipation and variable degrees of anaemia. – In sheep infected by large numbers of Haemonchus the conjunctiva (the mucous membrane that lines the inner surface of the eyelid and the exposed surface of the eyeball) can be snow white in colour.

- Heavy worm infestation results in progressive weight loss, weakness, a rough coat, loss of appetite, and oedema, particularly under the lower jaw – a condition termed as bottle jaw.

- Toxocara can cause in rapid breathing and coughing in young calves.

Note that egg counts are not always an accurate indicator of the number of adult worms present as egg laying is not always constant; some species of worms lay more or less eggs than others, and immature worms and larvae are not egg layers.

Some worms are much more aggressive than others. For example 100 Haemonchus worms in a lamb do as much damage as 5,000- 10,000 Ostertagia worms.

Read Also: Recommended Number of Ruminant Animals per Housing Unit for Fattening

Post mortem findings and Diagnosis

Adult worms are usually visible to the naked eye. Some are more easily seen than others. Worms may be only visible due to their movement in fluid stomach and intestinal contents.

- The mucus membranes are often pale.

- The carcass may be emaciated, but in some instances where an animal has been overwhelmed by a sudden massive invasion of larvae the carcass may be in good condition.

- The abomasum is frequently fluid filled and this may exend into the small intestine, especially in Haemonchus infestations.

- The liver is pale and fragile

- The alimentary tract will reveal worms when opened. Check especially the stomach, and the large intestine.

Prevention – Control – Treatment

Round worm infestation can be controlled through adherence to the following measures:

- In young cattle round worm infection can be controlled by the use of broadspectrum anthelmintics (drugs to expel worms) in conjunction with pasture management to limit reinfestation.

- Pasture management includes a move to clean pastures e.g. grass conservation areas or hay aftermath, or alternate grazing with other host species, or integrated rotational grazing in which susceptible calves are followed by immune adults.

- A special strategic treatment is required in sheep to counter the low immunity seen in ewes around lambing time. Treatment within the month before and the month after lambing should be given. Supportive management after treatment includes movement of sheep from contaminated pastures to cattle pastures, grass conservation areas, or pastures not grazed by sheep for several months. This period may vary from several weeks to several months depending on the weather pattern (longer if wet and cool, shorter if dry and hot).

- Resting pasture for more than 10 weeks will reduce the number of infective larvae on pasture. Separating young and mature animals in grazing paddocks or grazing different species of animals together. These practices will help to reduce parasite mass and reduce infestation levels.

- Better grazing management should avoid overstocking of animals on a particular paddock. Grazing management should also ensure that there are alternative grazing areas, should avoid damp grazing areas and always ensure that animals are in good condition. Well nourished animals are less likely to acquire heavy worm infestations.

Treatment

The following treatments and drugs are recommended for round worms.

- Albendazole should be administered orally at the end of the cold season and beginning of the dry season. The drug should be given at the rate of 10 mg/kg body weight

- Fenbendazole should be given at the end of the cold and beginning the dry season by mouth at the rate of 8 mg/kg body weight

- Ivermectin can be used in different forms such as injection, orally, or as a pour on. Should be given at the rate of between 0.2 – 0.5 mg/kg body weight as a subcutaneous injection. Giving anthelmintics by injection is recommended as it avoids the risk of damage to the animal’s throat through rough drenching and none of the drug is lost.

- Levamisole and oxyclazanide in combination should be given by mouth at 0.25 ml/kg body weight

- Albizidal antihelmintica as a botanical treatment- the leaves of the tree are fermented and sieved and administered orally.

NB. Always follow the manufacturer’s recommendations when administering drugs.

Read Also: Recommended Housing Design for Ruminant Animals

Common traditional practices

- Luo (cattle, goats, sheep): Cut about 2kg of fresh awayo (Rhus vulgaris) roots, put in 1 kg of water and leave overnight. Sieve and drench with 0.5 litre once a day for a week. Give half this dose for calves, goats and sheep. Give when it is cool and after the animal has eaten.

- Embu / Gikuyu (cattle, goats, sheep): Collect 2 handfuls of dry seeds of mugaita (Rapanea melanophloeos). Crush and mix with 1 litre of water. Boil gently for 20 minutes. Allow to cool, then drench once. For goats, sheep and calves use 500 ml; for large animals use 1 litre. Drenching should be done in the evening when it is cool. Repeat after 2 weeks.

- Kipsigis (cattle, goats, sheep): Crush 0.25 kg of matakarek (Rapanea melanophloeos) and mix in 1 litre of water. Let boil for 15 minutes. Allow to cool then drench the whole amount once. For small animals use 500ml; for large animals use 1 litre. Repeat after 3 weeks.

- Samburu (camels, cattle, goats, sheep): In the rainy season drive animals to areas with salty soils when the water has dried up. The animals will lick the salt from the surface of the ground.

- Maragoli (cattle, goats, sheep): Chop 2 bulbs of saumu (Allium sativum) and mix with 4 litres of water. Drench with 0.5 litres twice in 1 day. This treats worms and liverflukes. The dose is the same for adult cattle, sheep and goats.

- Somalia Ethiopia: Grind 2 fruits of Gosso (Hagenia abyssinica) in 0.5 of water . Drench a sick cow with this before it goes to pasture. Use half the amount for goats and sheep.

Read Also: Types of Hunting and their Negative Effects on Forest and Wildlife