I will strongly recommend that your ruminant animals should have access to water more than they have access to food. Water is very essential and the ruminant animals should not be denied it.

Most nomadic Fulani has a particular time when they normally lead their animals towards a water source. This should be done as regularly as possible because these animals need water for proper digestion of their feed and for their upkeep.

Ruminant livestock include cattle, sheep, and goats. Ruminants are hoofed mammals that have a unique digestive system that allows them to better use energy from fibrous plant material than other herbivores.

Unlike monogastric animals such as swine and poultry, ruminant animals have a digestive system designed to ferment feedstuffs and provide precursors for energy for the animal to use. By better understanding how the digestive system of the ruminant works, livestock producers can better understand how to care for and feed ruminant animals.

Water should be available always in the housing units of ruminants. The water also should be put in a cool and clean area of the pen. Water is required for life. Animals that serve humankind as sources of food, fertilizer, draught power, recreation, social status, and prosperity have an obligatory need for water.

Ruminant animals e.g., cattle, sheep, and goats hold a unique place in the human food web, able to consume highly fibrous feedstuffs e.g., forages often grown on land not suitable for other uses and by-product feeds, poor-quality protein feeds, or both, and convert them into high-biological-value nutrients and energy for humans.

It is important that this conversion by microorganisms mainly in the rumen and reticulum of the digestive tract and assimilation in the tissues of the ruminant requires sufficient water.

Read Also: How to control Ruminants from destroying Grasses where they graze

Importance of Ruminant Animals

The digestive system of ruminants optimizes use of rumen microbe fermentation products. This adaptation lets ruminants use resources such as high-fiber forage that cannot be used by or are not available to other animals.

Ruminant animals are in a unique position of being able to use such resources that are not in demand by humans but in turn provide man with a vital food source.

Ruminant animals are also useful in converting vast renewable resources from pasture into other products for human use such as hides, fertilizer, and other inedible products (such as horns and bone).

One of the best ways to improve agricultural sustainability is by developing and using effective ruminant livestock grazing systems. More than 60 percent of the land area in the world is too poor or erodible for cultivation but can become productive when used for ruminant grazing.

Ruminant animals like livestock can use land for grazing that would otherwise not be suitable for crop production. Ruminant livestock production also complements crop production, because ruminants can use the byproducts of these crop systems that are not in demand for human use or consumption.

Developing a good understanding of ruminant digestive anatomy and function can help livestock producers better plan appropriate nutritional programs and properly manage ruminant animals in various production systems.

Water Effects on Ruminant Animals Livestock Performance

Limitation of water intake reduces animal performance quicker and more dramatically than any other nutrient deficiency. Water constitutes approximately 60 to 70 percent of an animal’s live weight and consuming water is more important than consuming food.

Domesticated animals can live about sixty days without food but only about seven days without water. Livestock should be given all the water they can drink because animals that do not drink enough water may suffer stress or dehydration.

Signs of dehydration or lack of water are tightening of the skin, loss of weight and drying of mucous membranes and eyes. Stress accompanying lack of water intake may need special considerations. Newly arrived animals may refuse water at first due to differences in palatability.

One should allow them to become accustomed to a new water supply by mixing water from old and new sources. If this is not possible, then intake should be monitored to be sure no signs of dehydration occur until animals show adjustment to the new water source.

Water Requirements are Influenced by Physiological and Environmental Conditions

Consumption may vary greatly depending on the kind and size of the animal, physical state, level of activity, dry matter intake, quality of water, temperature of water and the environmental temperature.

The minimum requirement of water intake is reflected in the amount needed for body growth, fetal growth or lactation and that lost by excretion in urine, feces or perspiration.

Anything that influences these needs will influence the minimum requirement. Not all water must be provided as drinking water. Feeds that are high in moisture such as green chop, silage or pasture will provide part of the requirement, while feeds such as grain and hay offer very little moisture.

Water requirements are measured by voluntary up-take of water under a variety of conditions. Results imply that thirst is a result of need and animals drink to fill that need.

This is brought about by the increased electrolyte salt concentration in the body fluids which activate the thirst mechanism. Livestock may also increase water intake during hot months for its cooling effect.

Table 1 shows estimates of daily consumption of water for various livestock groups.

| Table 1 | |

| Estimated Gallons per Day | |

| Cows, Dry and Bred | 6 – 15 |

| Cows, Nursing | 11 – 18 |

| Bulls | 7 – 19 |

| Growing Cattle | 4 – 15 |

| Dairy Cattle | 15 – 30 |

| Sheep and Goats | 2 – 3 |

| Horses | 10 – 15 |

Read Also: Importance of a Sick Bay in a Ruminant House

Water Functions

Water in the body performs many functions. Water helps to:

- Eliminate waste products of digestion and metabolism,

- Regulate blood osmotic pressure,

- Produce milk and saliva,

- Transport nutrients, hormone and other chemical messages within the body, and

- Aid in temperature regulation affected by evaporation of water from the skin and respiratory tract.

Water Quality

Water quality, as well as quantity, may affect feed consumption and animal health since poor water quality will normally result in reduced water and feed consumption.

When evaluating water quality for livestock, consider whether livestock performance will be affected; whether water could serve as a carrier to spread diseases; and if the acceptability or safety of animal products for human consumption will be affected.

Most elements in water do not cause problems because they do not occur at high enough levels in soluble form. Cobalt, copper, iodide, iron, manganese and zinc may be toxic in excessive concentration but rarely are seen at levels high enough to cause problems.

Water quality problems affecting livestock are more commonly seen with high concentrations of minerals (excess salinity); high nitrogen content; bacterial contamination; heavy growths of toxic blue-green algae; or accidental spills of petroleum, pesticides or fertilizers.

Factors such as age, diet, condition and kind of animal determine tolerance of minerals in water. Decaying plant or animal protein, nitrogen fertilizer, silage juices and other factors may contribute to high levels of nitrogen forms in surface waters.

Water Access and Quality Improve Performance

Water access and quality can affect livestock performance. Farm managers with high producing dairy cows have reported substantial increases in milk output when cows have readily accessible water. Two to five additional pounds of milk per cow per day is not uncommon.

Pasture utilization can be greatly enhanced when animals do not have to travel far for water. A study from Missouri researched distances beef cattle traveled to water and how that affected grazing distribution and utilization of available forage.

The study results on the 160 acres tested showed that pasture carrying capacity could be increased an additional 14 percent by simply keeping livestock within 800 feet of water.

Other research from Wyoming concluded similar results under rangeland conditions. Their results showed cattle do 77 percent of their grazing within 1,200 feet of their water source. In this study, approximately 65 percent of the pasture was more than 2,400 feet from water, but supported only 12 percent of the grazing usage.

Read Also: How to Introduce New Animals into your Ruminant Farm

A study from Alberta, Canada, implies water quality greatly affects the ability of cattle to produce pounds of gain. As Table 2 indicates, animals in the test all averaged .5 lbs per day or more gain as a result of drinking trough (clean) water versus dugout/pond (muddy) water where reduced or negative gains resulted.

This research continues with a focus on animal performance. While other tests have not confirmed the same amount of increase due to water quality, generally it’s accepted that stale, poor tasting water can cause a reduction in water consumption and this type of water could be a host for disease organisms.

To evaluate water quality in relationship to livestock health problems, it is imperative to obtain a thorough history, make accurate observations and submit suspect water samples to a qualified laboratory if problems occur.

Other Effects

Today’s concerns about water quality for not only cattle, but human consumption lead to questions about care being given to the water resource.

Using a watering system where livestock do not have to have direct access to a stream or dugout/pond not only protects the water resource, but may also increase nutrient distribution throughout the field.

Through management of available water and tank placement, one can increase pasture productivity by promoting more uniform grazing. Uniform grazing results in uniform manure and urine distribution.

A grazing cow returns 79 percent of the nitrogen (N), 66 percent of the phosphorus (P) and 92 percent of the potassium (K) she eats to the pasture (Bartlett, 1996).

If allowed, livestock (ruminant animals) will move nutrients from the pasture and deposit those nutrients in locations not beneficial to pasture growth. Examples are under shaded areas or around water tanks.

A study from Missouri tested P and K levels of distribution in relationship to water placement. Soil test levels were not altered when water was less then 500 feet from the farthest part of the pasture. When stock had to travel 1,100 feet to water, changes in soil P and K were much greater nearer the water.

Read Also: Ideal Distance between a Ruminant Farm and Residential Areas

Ruminant Animals Feeding Types

Based on the diets they prefer, ruminants can be classified into distinct feeding types: concentrate selectors, grass or roughage eaters, and intermediate types. The relative sizes of various digestive system organs differ by ruminant feeding type, creating differences in feeding adaptations.

Knowledge of grazing preferences and adaptations amongst ruminant livestock species helps in planning grazing systems for each individual species and also for multiple species grazed together or on the same acreage.

Concentrate selectors have a small reticulorumen in relation to body size and selectively browse trees and shrubs. Deer and giraffes are examples of concentrate selectors.

Animals in this group of ruminants select plants and plant parts high in easily digestible, nutrient dense substances such as plant starch, protein, and fat. For example, deer prefer legumes over grasses. Concentrate selectors are very limited in their ability to digest the fibers and cellulose in plant cell walls.

Grass or roughage eaters (bulk and roughage eaters) include cattle and sheep. These ruminants depend on diets of grasses and other fibrous plant material. They prefer diets of fresh grasses over legumes but can adequately manage rapidly fermenting feedstuffs.

Grass or roughage eaters have much longer intestines relative to body length and a shorter proportion of large intestine to small intestine as compared with concentrate selectors.

Goats are classified as intermediate types and prefer forbs and browse such as woody, shrubby type plants. This group of ruminants has adaptations of both concentrate selectors and grass/roughage eaters. They have a fair though limited capacity to digest cellulose in plant cell walls.

1. Carbohydrate Digestion

a. Forages

On high-forage diets ruminants often ruminate or regurgitate ingested forage. This allows them to “chew their cud” to reduce particle size and improve digestibility. As ruminants are transitioned to higher concentrate (grain-based) diets, they ruminate less.

Once inside the reticulorumen, forage is exposed to a unique population of microbes that begin to ferment and digest the plant cell wall components and break these components down into carbohydrates and sugars. Rumen microbes use carbohydrates along with ammonia and amino acids to grow.

The microbes ferment sugars to produce VFAs (acetate, propionate, butyrate), methane, hydrogen sulfide, and carbon dioxide. The VFAs are then absorbed across the rumen wall, where they go to the liver.

Once at the liver, the VFAs are converted to glucose via gluconeogenesis. Because plant cell walls are slow to digest, this acid production is very slow. Coupled with routine rumination (chewing and rechewing of the cud) that increases salivary flow, this makes for a rather stable pH environment (around 6).

b. High-Concentrate Feedstuffs (Grains)

When ruminants are fed high-grain or concentrate rations, the digestion process is similar to forage digestion, with a few exceptions. Typically, on a high-grain diet, there is less chewing and ruminating, which leads to less salivary production and buffering agents’ being produced.

Additionally, most grains have a high concentration of readily digestible carbohydrates, unlike the more structural carbohydrates found in plant cell walls. This readily digestible carbohydrate is rapidly digested, resulting in an increase in VFA production.

The relative concentrations of the VFAs are also changed, with propionate being produced in the greatest quantity, followed by acetate and butyrate. Less methane and heat are produced as well. The increase in VFA production leads to a more acidic environment (pH 5.5).

It also causes a shift in the microbial population by decreasing the forage using microbial population and potentially leading to a decrease in digestibility of forages.

Lactic acid, a strong acid, is a byproduct of starch fermentation. Lactic acid production, coupled with the increased VFA production, can overwhelm the ruminant’s ability to buffer and absorb these acids and lead to metabolic acidosis.

The acidic environment leads to tissue damage within the rumen and can lead to ulcerations of the rumen wall. Take care to provide adequate forage and avoid situations that might lead to acidosis when feeding ruminants high-concentrate diets.

Read Also: How to Prevent Flies on a Ruminant Farm

2. Protein Digestion

Two sources of protein are available for the ruminant to use: protein from feed and microbial protein from the microbes that inhabit its rumen.

A ruminant is unique in that it has a symbiotic relationship with these microbes. Like other living creatures, these microbes have requirements for protein and energy to facilitate growth and reproduction.

During digestive contractions, some of these microorganisms are “washed” out of the rumen into the abomasum where they are digested like other proteins, thereby creating a source of protein for the animal.

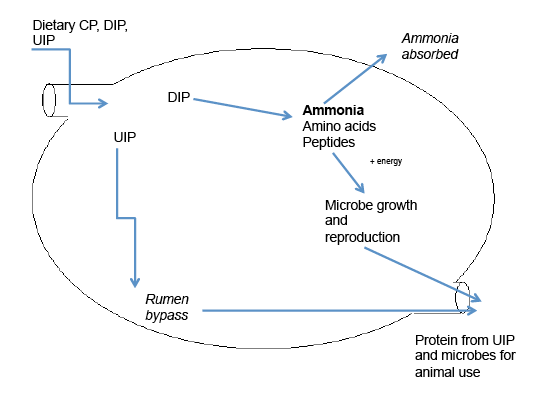

All crude protein (CP) the animal ingests is divided into two fractions, degradable intake protein (DIP) and undegradable intake protein (UIP, also called rumen bypass protein).

Each feedstuff (such as cottonseed meal, soybean hulls, and annual ryegrass forage) has different proportions of each protein type. Rumen microbes break down the DIP into ammonia (NH3) amino acids, and peptides, which are used by the microbes along with energy from carbohydrate digestion for growth and reproduction.

Excess ammonia is absorbed via the rumen wall and converted into urea in the liver, where it returns in the blood to the saliva or is excreted by the body. Urea toxicity comes from overfeeding urea to ruminants. Ingested urea is immediately degraded to ammonia in the rumen.

When more ammonia than energy is available for building protein from the nitrogen supplied by urea, the excess ammonia is absorbed through the rumen wall.

Toxicity occurs when the excess ammonia overwhelms the liver’s ability to detoxify it into urea. This can kill the animal. However, with sufficient energy, microbes use ammonia and amino acids to grow and reproduce.

The rumen does not degrade the UIP component of feedstuffs. The UIP bypasses the rumen and makes its way from the omasum to the abomasum. In the abomasum, the ruminant uses UIP along with microorganisms washed out of the rumen as a protein source.

In summary, monitoring water intake for livestock (ruminant animals) is mandatory for a farm manager. Ample supply of good quality water is necessary for maximum production. Consumption of water is determined by many factors and basic life functions require it.

Easy access to quality and plentiful water supplies may increase livestock productivity. Management of the water source can lead to more uniform distribution of nutrients excreted through livestock waste. Sound environmental practices may be enhanced by correct use of a water source.

Read Also: How to Find the Best Recycling Center for Your Recycling Needs